For over four years, TGPWU has also been involved in an agitation demanding basic infrastructural support for drivers at the Rajiv Gandhi International Airport (RGIA) in Hyderabad (Salauddin and Afsar 2025). The airport is about 25 kilometers from the city center, making it a relatively long ride for drivers who ply their cabs within the city, and which necessitates long waiting times. Despite aggregator platforms offering airport cab services for over than a decade across Indian cities, only customer-facing infrastructural changes such as boarding zones and lanes have been considered a priority and built, with designated waiting zones for drivers remain inaccessible or absent outside of the pickup area. At RGIA, drivers were initially allotted an open, unshaded parking lot to wait in, without access to basic amenities like washrooms, rest areas, or drinking water. The implicit expectation was that they endure harsh summers and monsoons while waiting for bookings. TGPWU's campaign demanded a proper waiting area with a water cooler along with washroom access, building public consensus in their support through offline and online mobilisations and demonstrations. This demand was finally met in 2024 with the construction of a rest area (see figure 6) and dedicated washrooms being provided for drivers at the airport.

Extreme climate events—heatwaves, urban flooding, and infrastructural failures—are now common in Indian cities. Mumbai floods annually, Bangalore's foaming lakes and waterlogged roads are as frequent as its traffic woes, Delhi's smog is as iconic as its landmarks, and Hyderabad's heatwaves aggravation intensifies each year. Meanwhile, the gig economy has become a significant source of livelihood for a large section of urban residents. Plying cabs and bikes across the city while lugging heavy loads, platform-based gig workers include delivery workers, cab drivers, beauty workers, home service workers, and logistical support workers, employed in the “booming digital economy” in India (Niti Aayog 2022). Often hailing from low-income backgrounds, many of these workers are climate migrants impacted by famines or excessive rainfall in their native regions. As new entrants to the city, they transition from rural livelihoods to daily wage and informal work in urban centres (Surie and Sharma 2019). Here, many of them find app-based work attractive, given its promise of flexible hours and better earnings, and rely completely or partially on it to supplement their incomes (Deb and Roy 2025). However, extreme weather events increasingly also impact urban livelihoods, with gig workers being at the forefront. These intersections between climate politics and labor struggles in urban contexts thus warrant more attention.

For location-based gig workers, the city is their workplace (Das and Bhat 2025). Being constantly on the move, they travel long distances, and remain on the road for several hours, often relying on urban public spaces and amenities for basic needs like water and sanitation. This makes them profoundly vulnerable to urban infrastructural failures and extreme weather events. The impact of climatic shifts in workers’ everyday lives is further intensified by exploitative labor relations within the platform economy and a severe lack of infrastructural support. Algorithmic management-induced uncertainties and uneven urban environments intensify gig workers' daily struggles to access necessities like water and washrooms in cities (ibid). Meanwhile, platforms profit immensely from their labor, subsidizing operation costs through gig work, while offloading the risks associated with the embodied work of delivery and facilitating mobility onto the workers, come rain or sun. The lack of infrastructure, social protection, and regulatory oversight creates a precarious reality that compounds the effects of climate change, creating dystopian scenes: workers wade through floodwaters on their bikes to avoid penalties, drive under a scorching sun without drinking water, and sleep on footpaths and roadsides to catch a break. Ongoing collectivization efforts within the platform economy and the consolidation of the broader gig workers’ movement has resulted in unions and federations being formed to advocate for more structured interventions towards social security ends. But the consideration of climate-related issues in policy and advocacy debates remains limited and is only beginning to be addressed within these spaces.

In this case study, I focus on the work of two gig worker organizations—Hyderabad-based Telangana Gig and Platform Workers’ Union (TGPWU), and Delhi-based Gig Workers’ Association—whose advocacy efforts aim to fill this gap. Drawing on long-term ethnographic engagement with platformization trajectories in urban contexts and the emergent gig worker movements, I discuss three specific campaigns that have strategically used climatic shifts and extreme weather events to underscore the urgency of these issues and reinvigorate labor politics in urban India. Each campaign highlights how gig workers’ issues and experiences of/in the city are refracted by urban environments, both built and natural, as well as across sectors of work.

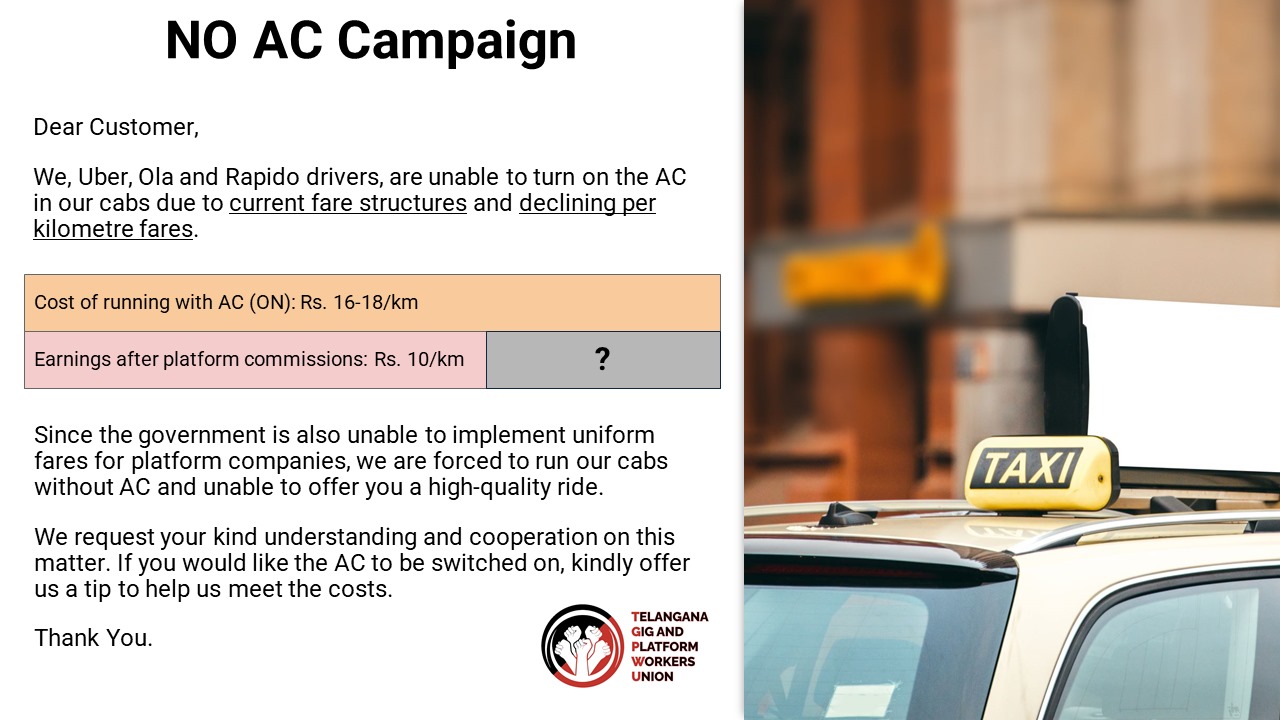

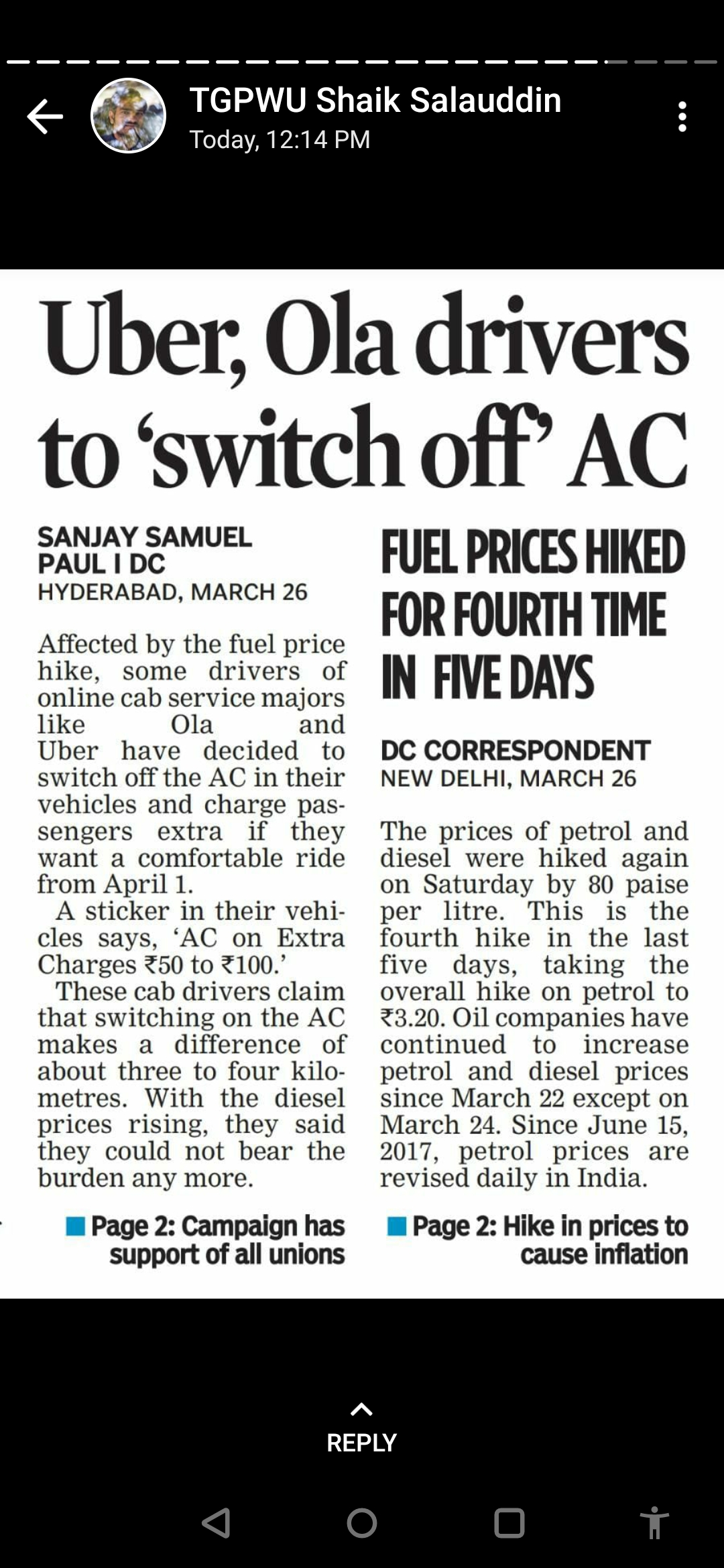

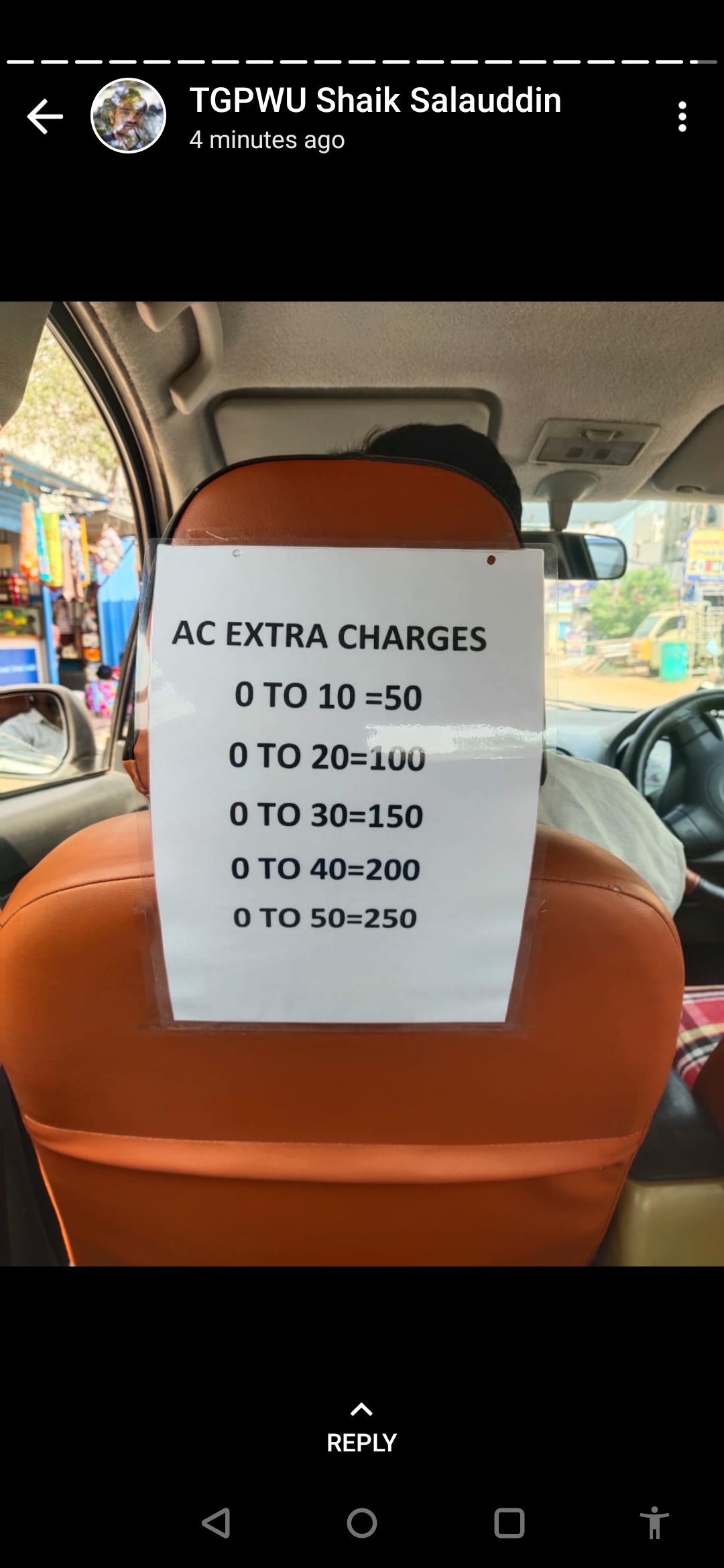

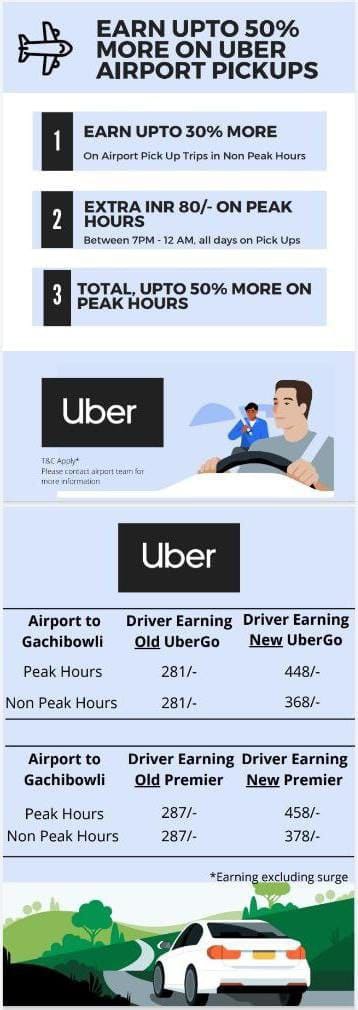

In April 2022, TGPWU launched the ‘No AC campaign’ in Hyderabad (TGPWU 2022, Bhat 2022). Citing low fares and rising fuel prices, Ola and Uber drivers protested by switching off their cars' air conditioning during peak summer. They requested a symbolic surcharge from customers to turn it on, aimed at building awareness amongst customers and to increase public pressure on platform companies. Fostering solidarity between customers and drivers, the campaign successfully encouraged several customers to contact platforms and urge them to address drivers’ concerns, amplifying the union’s demand for higher base rates to match the inflated prices. Relaunched annually (TGPWU 2024), this campaign keeps the issue of low fares and extreme heat in the public eye, as recorded temperatures consistently touched the 40-degree mark.

Addressing the absence in public understanding of climate change's impact on precariously employed gig workers, the campaign revealed the complex calculus workers have to undertake to sustain their livelihoods. By leveraging a scorching urban summer as a critical moment to draw attention to workers’ issues, it translated the immaterial and affective experience of heat by pulling focus towards its embodied and material costs. Using the air conditioner as a tool of resistance, this collective effort foregrounds the political aspects that shape the technological and the environmental. The demand for extra payment, while causing friction at times, unsettled the "digital veil" that separates customers and workers. The cab became an affectively charged political space where the shared experience of urban heat created the possibility for cross-class solidarity between relatively more privileged urban resident-consumers and working class urban resident-drivers, transforming a digitally prefigured mundane social interaction into a political act that helped assert workers’ agency, and catalyse social change in urban contexts.

For over four years, TGPWU has also been involved in an agitation demanding basic infrastructural support for drivers at the Rajiv Gandhi International Airport (RGIA) in Hyderabad (Salauddin and Afsar 2025). The airport is about 25 kilometers from the city center, making it a relatively long ride for drivers who ply their cabs within the city, and which necessitates long waiting times. Despite aggregator platforms offering airport cab services for over than a decade across Indian cities, only customer-facing infrastructural changes such as boarding zones and lanes have been considered a priority and built, with designated waiting zones for drivers remain inaccessible or absent outside of the pickup area. At RGIA, drivers were initially allotted an open, unshaded parking lot to wait in, without access to basic amenities like washrooms, rest areas, or drinking water. The implicit expectation was that they endure harsh summers and monsoons while waiting for bookings. TGPWU's campaign demanded a proper waiting area with a water cooler along with washroom access, building public consensus in their support through offline and online mobilisations and demonstrations. This demand was finally met in 2024 with the construction of a rest area (see figure 6) and dedicated washrooms being provided for drivers at the airport.

While the previous campaign is a more direct response to an extreme weather event, this particular struggle highlights a critical distinction: while extreme events are starkly visible and elicit urgency more readily, the everyday, cumulative effects of the climate crisis on marginalised populations are often invisible and call for persistent and enduring interventions. The campaign's success underscores how collective struggles for basic amenities are simultaneously a response to climate change and are imperative for highlighting multi-dimensional vulnerabilities for marginalized groups. Gig workers' fight for restrooms and shaded areas reveals the fundamental dissonance between capitalist economic systems and worker wellbeing, indicating the inability of profit-driven business models to account for the physical realities of working in a changing climate. By drawing attention to infrastructure, these collective efforts not only improve working conditions, albeit in a patchwork manner, but also expose how urban economies are failing to adapt to the environmental crises they exacerbate.

In the summer of 2025, the Delhi-based Gig Workers’ Association, in collaboration with the Amazon India Workers’ Union and the Heat Wave Action Coalition, launched the #CoolDeliveries campaign. Adopting an appeal-based approach and timed for World Environment Day, the online campaign aimed to raise awareness about the heat stress faced by delivery workers. While the organization has broader demands for social security, this campaign aimed to build consumer literacy and empathy. The campaign used artistic imagery and mixed-media methods such as comic strips, explainer guides, in social media carousels and reels to convey the affective and embodied experience of delivery work. These media showcased the visceral experience of a worker on the job—the asphalt burning their feet, phones and bikes overheating, ferrying temperature sensitive items in a hurry, navigating traffic, driving on smog-choked or waterlogged streets. They also highlighted the underlying caste politics in urban contexts that discipline working class bodies by curtailing access to shared spaces within enclaved societies (e.g. elevators), or by enforcing temperature monitoring, time logging, and professional grooming standards. Finally, the campaign flagged the urgent need for climate-sensitive measures, such as hazard pay, the establishment of cooling zones across cities, breathable uniforms, emergency services, gender-sensitive support, healthcare support, and insurance and payment models that account for extreme weather when evaluating work and applying penalties.

Invoking support from civil society actors and consumers through public action, the #CoolDeliveries campaign acutely conjoins labor struggles with climate politics. By publicizing workers' adaptive practices—like carrying blankets for impromptu rest stops or covering phones with soaked handkerchiefs—and highlighting specific challenges, such as women workers’ struggles to find a clean washroom (Das and Bhat 2025), the campaign combined the need for consumer awareness with a deeper structural critique. Foregrounding glaring infrastructural gaps in Indian cities that render them immensely hostile as workplaces for gig workers, it underscores the compounded nature of the climate crisis (Westman et al 2022) in Indian cities. The campaign serves as a powerful reminder that addressing climate crisis, and accounting for its multi-layered effects on marginalized populations, requires multi-pronged measures, including policy changes to improve working conditions as well as a shift in consumer consciousness to make more immediate relief available to workers.

These campaigns highlight the unequal nature of Indian cities and challenge the normalization of the climate crisis's uneven impact. Collective action forces us to measure changing temperatures or unusual rainfall patterns not in degrees or millimetres, but in terms of the human cost borne by gig workers—while making a delivery in heavy rains, or driving to pick up a customer in the scorching heat only for them to cancel. These campaigns also help imagine the possibility of building solidarities transversally, through research initiatives that highlight the impacts of heat stress on workers across sectors such as women workers in garment factories (HeatWatch 2025) or documenting experiences of workers in other parts of the digital economy’s supply chain such as in an Amazon warehouse (Ali 2023, UNI Global Union 2025 ). Further research at this intersection, geared towards building cross-sectoral connections and synergies between movements can help highlight the shared concerns and challenges that workers face due to climate change shocks and extreme events, across the board. Nonetheless, even if the impact of these campaigns on workers’ everyday lives might be gradual and incremental, these collective efforts are invaluable for workers’ self-organisation and more importantly, have succeeded in bringing labor issues to the forefront of urban discourse. Centring workers' voices against the backdrop of a celebratory digital economy and reframing the urban space as a site of political contestation and collective action is a win that should be celebrated widely, even as conversations on these issues and the journey towards climate justice within the platform economy is only just beginning.

Ali, T. Ali, T. (2023) “The global fight to organise Amazon”, Tribune Magazine, 10 October.

Bhat, A. and Das, A. Das, A. and Bhat, A. (2025) “Placing platform workers in the city’s urban imagination,” Question of Cities.

Deb, D. and Roy, S.D., 2025. “The Twin Realities of Indian Platform and Industrial Capitalism: A Study of Migrant Workers in National Capital Region (NCR).” In Deindustrialization and Economic Restructuring in Post-Reform India (pp. 139-164). Routledge India.

Gig Workers’ Association Gig Workers’ Association (2025) #CoolDeliveries campaign [Facebook reel], 11 June.

HeatWatch HeatWatch (2025) “Heat stress and workers' rights” [LinkedIn post], 11 June.

Press Information Bureau (2022) NITI Aayog releases "India’s Booming Gig and Platform Economy" report, 27 June.

Rest of World Rest of World (2022) “The No AC campaign: Uber and Ola drivers in India protest low fares,” 13 April.

Salauddin, M. and Afsar, R. (2025) “At Hyderabad airport, drivers agitate for the bare minimum” Question of Cities.

Surie, A. and Sharma, L.V., 2019. “Climate change, Agrarian distress, and the role of digital labour markets: evidence from Bengaluru, Karnataka.” Decision, 46(2), pp.127-138.

Telangana Gig and Platform Workers’ Union (TGPWU) Telangana Gig and Platform Workers’ Union (2022) Campaign: Ola and Uber drivers in TGPWU conduct ‘No AC Campaign’ to demand higher fares, 29 March.

Telangana Gig and Platform Workers’ Union (TGPWU) Telangana Gig and Platform Workers’ Union (2024) Telangana Gig and Platform Workers’ Union (TGPWU) announces ‘No AC Campaign’, 22 April.

Westman, et al. Westman, L., Vähä, M., Lehtonen, S. and Kankaanpää, K. (2022) ‘Compound urban crisis: Climate-related risks for vulnerable urban systems’, Climate, 10(4), p. 57.