From neighborhoods and restaurants segregating meat-eaters from vegetarians, to vegetarian-only rental advertisements, to the caste-class composition of flood-prone slums, to the untouchability protocols dehumanizing domestic workers, caste is the structuring logic of Bengaluru’s spaces and ecologies. Yet, the city’s privileged castes, comprising of brahmins, lingayats, jains, vokkaligas, and other dominant land-owning castes, deny casteism. They rail against reservation (affirmative action quotas), even though they have long benefited from structural casteism. Middle-class environmentalists (typically from dominant castes), moreover, seek to conserve the city’s green spaces and lakes by ridding it of “dirty” and “encroaching” slums—evicting Dalit-Bahujan and Muslim settlements to the outskirts—even as these same elite groups construct real estate on sensitive lakes and wetlands and deploy oppressed caste and poor migrant labor to do so.

In this blog post, I offer brief remarks on the role of eco-casteism and brahminism in Bengaluru’s ongoing caste segregation and climate apartheid. I write from the vantage of a dominant caste scholar of environmental casteism and environmental racism, recognizing the caste-class privileges that I continue to benefit from and am complicit in, including living a supposedly “casteless” cosmopolitan life between India and the U.S. I thus write with the aim of exposing how caste power operates in the urban environment, including by reflecting on my own ongoing anticaste journeys.

Mukul Sharma has coined the term “eco-casteism” to refer to both the denial of caste prejudice in India’s ecological movements, and to the naturalizing of caste hierarchy as harmonious and sustainable in Gandhian environmental discourse. The upholding of “brahminism”— an ideology that sanctifies the brahmin as the most ritually “pure” and at the top of the hierarchy with all other castes beneath him as “polluted”—was to India’s foremost modern anticaste intellectual, lawyer, and statesman, B.R Ambedkar, plainly, a case of the “negation of the spirit of liberty, equality and fraternity.” Meanwhile, “climate apartheid,” as used by Jennifer Rice et. al. refers to the racially and spatially uneven nature of climate change vulnerability, in which poorer, laboring groups are deemed expendable and risk most from extreme weather events while they bear the least responsibility for climate change. In India, climate apartheid is inseparable from caste apartheid, or the spatial segregation of residential neighborhoods, schooling, and cultures by caste (see especially the work of Bharathi et al. and Kuttiah). Climate apartheid also manifests through elite environmentalists’ appropriation of conversations related to climate change, as Uday Kukde argues, and to the erasure of Dalit-Bahujan human-nature relations, as Pradnya Mangala has written.

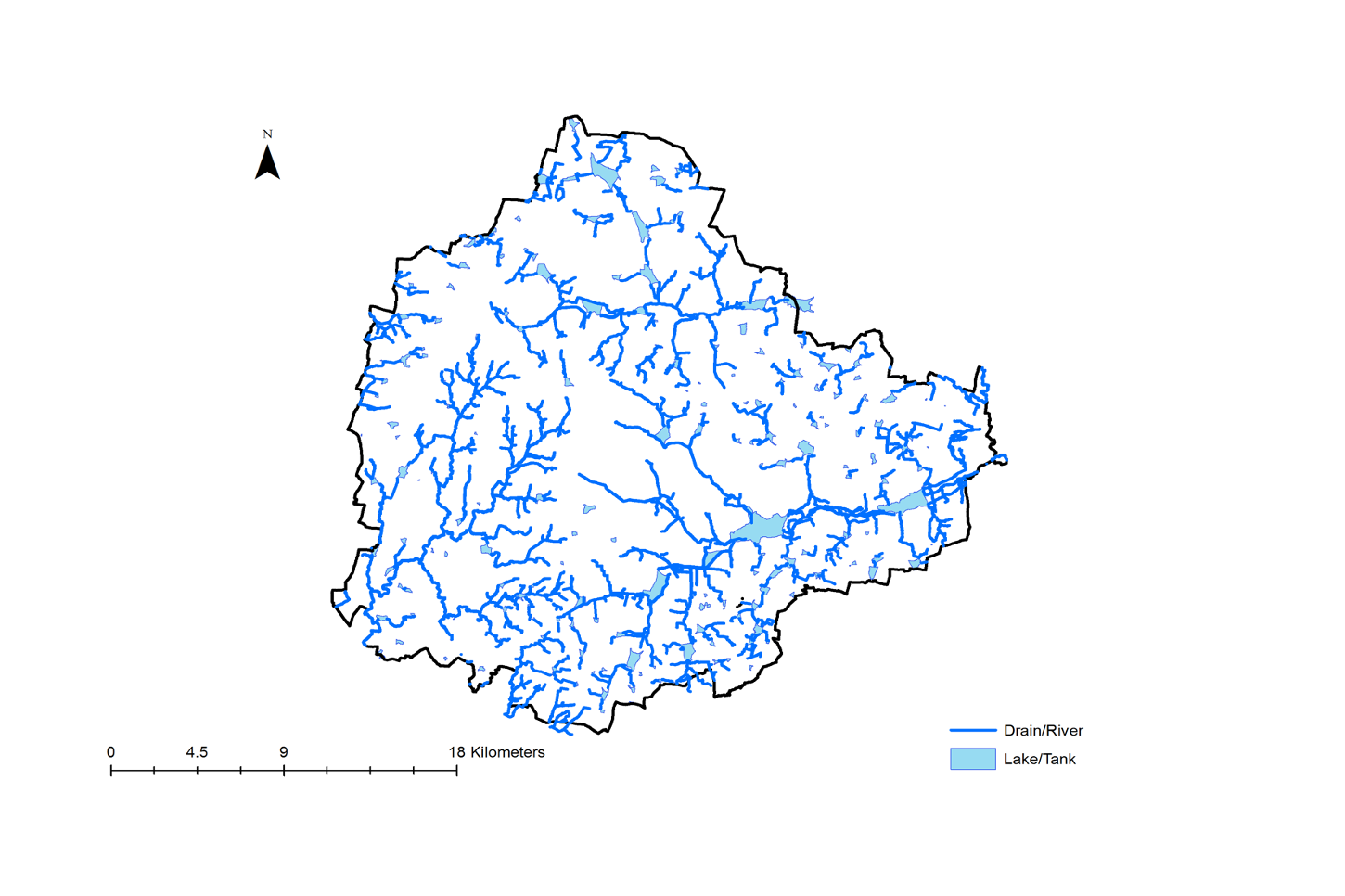

In Bengaluru, a city dotted with ancient, interconnected water harvesting systems known as keres (lakes) and raja kaluves (storm drains), lake conservation is a popular activity among privileged environmental activists. As an urban geographer whose family lives in a Bengaluru apartment complex surrounded by “dying” lakes, I found myself at first seduced by lake activism—what can be more enticing than a new jogging track around a rejuvenated lake where trash has been dredged out and migratory birds have now returned to nest? These restored lakes promise to serve as serene refuges among the chaos and pollution of city life. I attended lake conservation meetings, read scientific reports, and toured restored lakes with middle-class activists. But the more I learned about lake conservation, the more I understood that it is not an inclusive process. Those vested in conserving urban ecologies equally need to question how their “bourgeois environmentalism,” as Amita Baviskar calls it—their preferences for recreation and green aesthetics—is subtly rooted in caste-class power.

From the late colonial period at the end of the 19th century, as distant piped water became the preferred source of drinking water for the city, Bengaluru’s lakes were reduced or repurposed for recreation and real estate, including for residential layouts, cricket stadiums, and golf courses. It is only recently that lakes have been revalued as ecological commons worth saving. Lakes may well be ecological “commons,” but this is a politically laden assumption, as Jayaraj Sundaresan argues; different classes, castes, and communities effectively have unequal access to and power over the commons. Researchers Amrita Sen, Hita Unnikrishnan, and Harini Nagendra find that poorer Dalit castes, such as the Voddars and Adi Karnatakas, who once helped build and now depend on lakes for livelihood, foraging, and grazing their livestock, for instance, have been systematically excluded from access via corporate-led lake privatization and elite capture of lake decision-making. With the city becoming more concretized, and with unpredictable monsoonal patterns, flooding from overflowing lakes is increasingly common. An underlying logic of climate apartheid is at play when courts, environmentalists, and bureaucrats criminalize Dalit-Bahujan slum dwellers inhabiting lake beds, blaming them for flooding and pollution—further exacerbating the exclusionary lake governance I described above. Meanwhile the encroachments of middle-class apartments, Hindu temples, and gaushalas (cow sheds) are left untouched, especially in an era of Hindutva sanction and rule, as journalist-activists at Slum Jagatthu, Issac Arul Selva and Siddharth K.J. have reported.

Walking around the jogging track fringing a lake near my apartment building, I can see a slum sitting in adjacent to a middle-class layout and a gated apartment complex on the lake banks. A middle-class resident welfare association has been fighting a protracted battle to dislodge the slum residents, over half of whom are from the Adi Karnataka (Dalit) caste and half are from the Tigala (other backward classes) caste. Landless laborers from drought distressed Ramanagara district, these slum residents migrated to Bengaluru two decades ago. The grounds for evicting the slum are environmental and legal—a way of “illegalizing the poor”—as Leo Saldanha refers to it. Such evictions are also caste laden because of the structural inequalities built into the housing system in the city. This particular slum is standing its ground and fighting for better resettlement housing, but whether or not its residents will garner humane living conditions in the resettlement location is uncertain.

Nearby, others are not so successful. As I walk around a slushy potholed road ringing another lake, the wreckage from a demolition drive ordered by a court judgement was visible: bulldozered debris from low-lying informal settlements, piles of people’s shattered belongings, fences marking off demolished areas from public access. A nearby lower-class Muslim settlement teetering on the edge of a major storm canal had met with the same fate: it had been targeted for eviction in the city’s bid to “flood proof” the city. Yet, as I walked around the demolished houses, the city engineer I was accompanying admitted that it was an adjacent IT back-office—with its blue-faced glass windows and appropriate “world-class” aesthetics as D. Asher Ghertner argues—that was responsible for blocking storm flows in the area. The Muslim “encroachment” was removed; the IT back-office was not.

This is the driving logic of climate apartheid. Climate apartheid wrought by eco-casteism and brahmanism mean that marginalized castes experience multiple vulnerabilities: they are excluded from urban governance and environmental decision-making; their manual scavenging labor is recruited to clear fetid floodwaters, as Shreyas Sreenath has documented; and they are targeted because they live in informal and easy-to-blame and easy-to-evict “encroaching” settlements. Flood proofing is selective, carefully calibrated to preserve caste, class, and environmental privilege for the few, while rendering others evermore expendable. An anticaste praxis would seek to democratize land and lake governance, tethering ecological ideals to social justice priorities. Some hopeful signs lie in the Environment Support Group, a Bengaluru non-profit, pushing the Karnataka High Court to pass a 2021 judgement to decentralize lake governance by involving locally elected bodies. However, it remains to be seen whether decentralized environmental governance can indeed be anticaste, anti-brahmanical, rehumanzing, and socially just.