What kinds of stories can palimpsestic drawings tell us about the process and experience of changing urban environmental and social climates in South Asia? I provide one response to this question by looking from Malad, formerly along Mumbai’s periphery, dotted with fishing villages, and now a prominent service sector hub. Digital collages serve to illustrate changes in Malad’s urban morphology resulting from a long history of colonial and postcolonial land transactions that facilitated infill and land reclamation. The palimpsest reveals the ensuing environmental and livelihood damage in the form of toxicity, reduced fish availability, and loss of other environmental resources, absent in the dominant narrative surrounding Malad’s transformation. Environmental associations of livelihood and loss are uneasily juxtaposed with marketized sustainability narratives that frame service sector development. The palimpsest represents the power nexus involved in transforming urban environments with repercussions on urban ecological systems, and which erases associations held by indigenous communities.

In this annotated photo essay, I elaborate on insights from each layer of the digital collage, before returning to some broad takeaways.

pa·limp·sest

“scroll of parchment on which a new text is written after the original writing has been made invisible, or the canvas on which a new painting is painted over the old one, [wherein] the old texts and paintings come shining through the surface” (Engbersen 2001, 126).

pa·limp·sest [as a conceptual analytic]

“multilayered structure that emphasizes the coexistence of multiple visions of different cultures on the landscape” (Mitin 2017, 2)

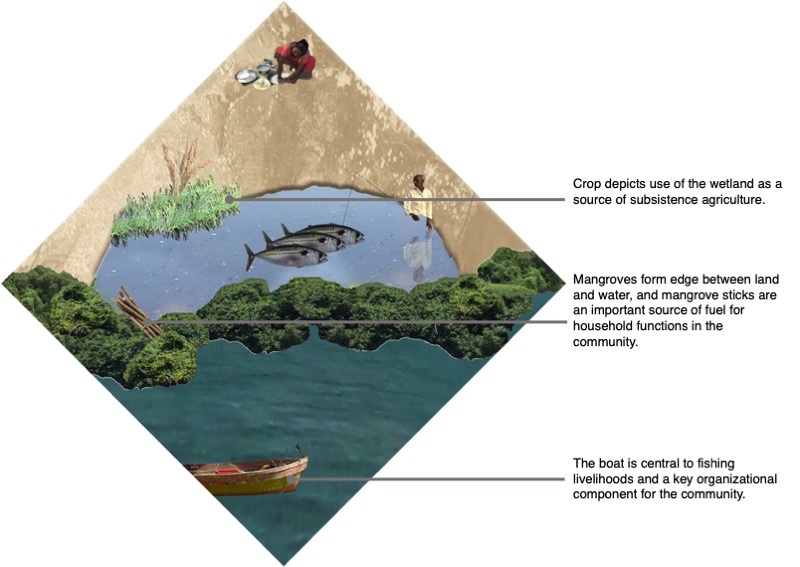

The first collage shows pre-British impressions and associations with what is now Mindspace Malad. Fisher folk in Malad explained that their ancestors had engaged in fishing activities since a “long, long time, since before the British arrived, before what we know as Bombay [or now Mumbai] existed.”

Historically, the wetland (now Mindspace Malad, a service sector hub) – seen here amorphously demarcated from its watery and land-based surroundings – was used as an ecological common before the British “gifted” the site to an elite Parsi family. The motifs here include a boat, mangroves, fish, an agricultural crop, a man fishing while standing in the wetland, and a woman preparing a meal at some distance from it.

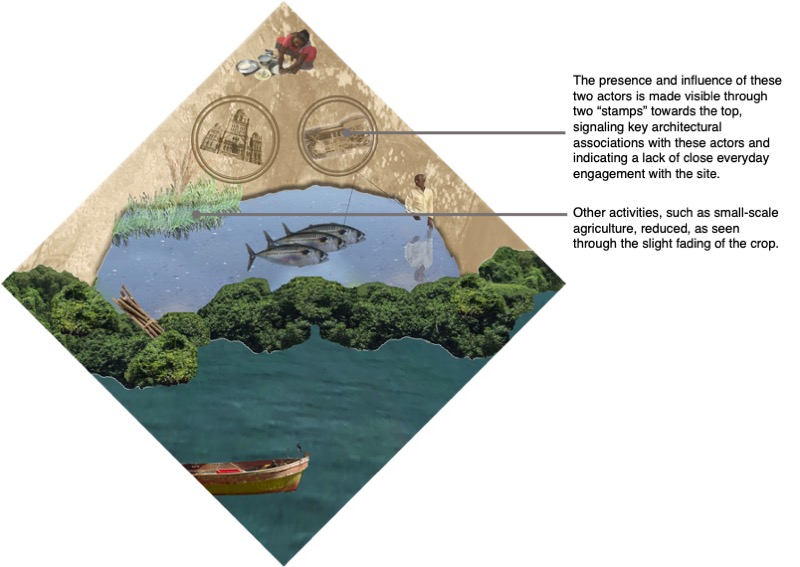

The second collage shows land transactions between the British colonial government and the Dinshaws, an elite Parsi family. The British gifted the Dinshaws the wetland for their loyalty.

The transaction had short and long-term consequences. In the short run, Bhandarwada residents had to pay rent to continue fishing here. Their consent was required for any other land transaction.

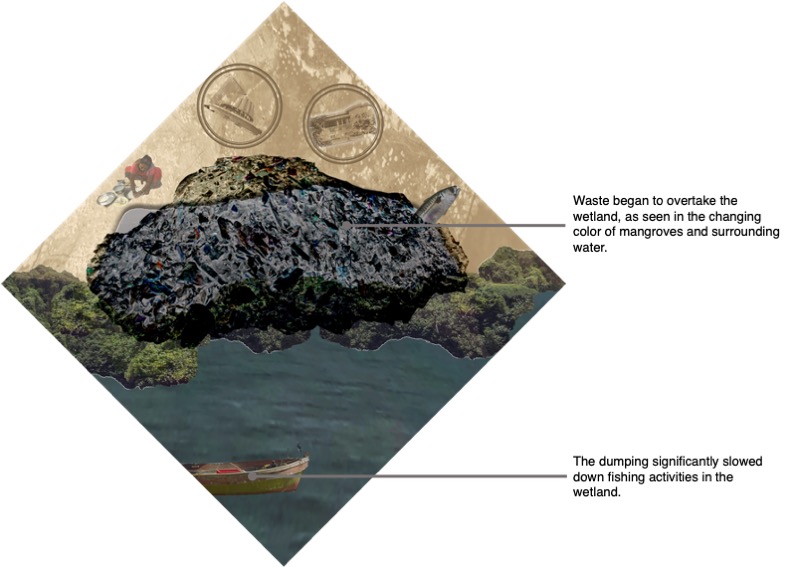

The third collage shows a pivotal moment marking the transformation of this area. The Indian nation-state began dumping garbage here in 1968. Bachoobai Dinshaw, who inherited the property from her brother, made Wadia the administrator of the estate in 1972.

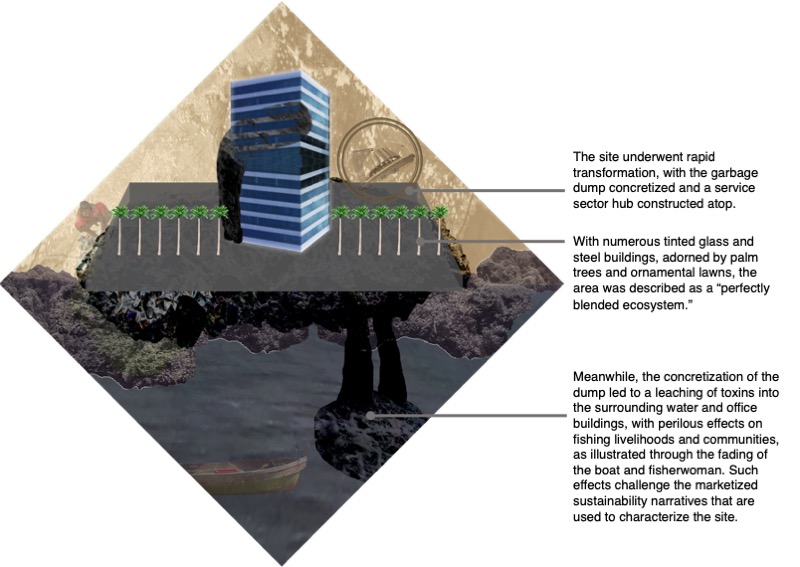

The final collage shows change that have occurred in the last two decades. The garbage dump closed in 2002, the Wadias sold the land to K.Raheja. Many land contestations followed, with the K.Rahejas ultimately prevailing. Bhandarwada residents were unaware that the transaction had occurred, realizing something was underway when construction activity commenced, which they contested on legal grounds. This led to some back-and-forth, with contestations still underway.

The decreasing ability of fisher folks to manage and access land and water is depicted through a slow fade across the collages. We see an emphasis on activities of fishing, mangrove sticks, small-scale agriculture, and fisherwomen’s household activities, whose layered histories unsettle dominant narratives about the area.

The palimpsest helps visualize toxic flows that leach into the water, float somewhat uncertainly into the building, creating a persistent yet ephemeral smell, and are not fully identifiable, yet are posited to have grave impacts on human and environmental health. This toxicity accumulates in the bodies of people, sea creatures, and plants, forming an absent presence that characterizes the site.

I juxtapose different associations and relations with the environment, complicating narrow aesthetic conceptions of the environment and illustrates how a prioritization of marketized “sustainable” development can detrimentally impact indigenous practices that treat the environment as a resource for subsistence and livelihood.

The last collage captures the intensity of contemporary development and its contrast with earlier modalities. The quick developmental shifts lie in contrast with the pace of fisher livelihoods, which are in tune with tidal and seasonal shifts. The toxicity in land, water, and air – and in the bodies of those who work in Malad is constituted by a slow and seeping temporality.