On an unusually warm day in June 2025, I attended a climate finance event in London as part of the London Climate Action Week — an annual occurrence featuring conferences and seminars organised by climate researchers and practitioners across the city. A representative of an international bank in Japan was on stage and remarked, “Is it fair that we are giving debt, if it is for adaptation and resilience?” Their question was a rhetorical one, and likely meant to set up a counter argument, since their organisation was in the business of lending. Nevertheless, it was an acknowledgement of a prevailing idea that has gained momentum in the mainstream climate and finance community recently. Namely, not all debt is equal, and some kinds of debt can undermine development and climate action.

The governing principal of development finance is that money, whether public or private, can be a lever to unlock progress across scales. In the same vein, finance to help communities and systems overcome the impacts of climate change has been framed as adaptive. But there is an acknowledgement that the terms on which money is given, especially to poorer countries, matters. Previously at the margins of development thinking, this idea underwent a resurgence in 2022 when Mia Mottley, the Prime Minister of Barbados underscored the plight of nations that periodically lost more than their annual GDP to extreme weather events and yet diverted considerable sums of money each year to service their international debt.1 Money, Mottley argued, that could have been spent on development and disaster preparedness.

Today climate and development practitioners agree that debt adds to the financial and climate vulnerability of many Global South nations. It is commonplace to hear international financial institutions and consultants refer to the ongoing “reform” of the international financial system.2 It includes efforts by governments and development organizations to find ways to re-engineer and repackage public and private finance to global south nations on “better terms,” to help them meet their sustainable development and climate targets.3

But finance on better terms for nations doesn’t necessarily translate to improved modes of finance to communities.4 Mainstream finance, which is currently preoccupied with the inequity of debt at the macrolevel, has been curiously silent on the impacts of debt and indebtedness to households at the microscale. Workshops, conferences, and reports reference a “paradigm shift in the discourse on scaling capital flows and reshaping the financing system”5 but do not delve into the need for a similar transformation in finance to communities. Rather, a recurring solution to making climate-impacted households resilient is more debt.

At another an event in London, I heard development finance organisations talk about their efforts to climate proof banks and microfinance institutions against disasters and climate change. Solutions included “top-up loans” to communities in Bangladesh during cyclones, bundling weather-linked insurance with microcredit, and helping microfinance institutions become “digital first” so extreme weather events were not a physical impediment to financing. These solutions build on the logic that timely access to funds during disasters can help households tackle immediate losses, smooth income gaps, and better manage relief and recovery. Such efforts, however, do not question why communities must bear the additional financial costs of climate change, nor do they tackle the fundamental problem of indebtedness.

It's late December in 2024 and I’m in Somwati Devi’s thatched house in rural Eastern Uttar Pradesh (UP). Two men are sitting on a wooden cot outside. Somwati is squatting on the floor, face partially covered by her sari. The men, Jagdeep and Raja, are from microfinance companies. They are waiting for borrowers to come and pay their loan instalments. Women in this part in UP do not normally participate in joint meetings. Many tell me that it is a humiliating process, and they prefer to deposit their money and leave or send it through relatives. The few women who wait around are there to plead their case. Somwati doesn’t have the money today. Jagdeep grumbles, “Is gaon ki credit kharab hai (The village has a spoilt credit record). This centre (borrowing group) has 23 members and 13 are yet to pay. Sochte hai bauji ka bank hai (They think it’s their father’s bank).” Somwati counters, “I used to pay on time. My husband who mixes cement in the village took an advance from his contractor and used it up, where will I get the money? Things have been difficult over the last three-four months.”

Somwati’s family are sharecroppers. Like many Dalits in the village, they work in low-lying fields that get inundated every year during the monsoons when the tributaries of the Rapti river overflow. I ask Somwati about her Kharif harvest. She explains that the rains came early, and her family lost the corn they sowed on one bhiga (a third of an acre) of shared land. They subsequently planted rice in the water-logged fields but only recovered half the harvest because the rains continued to be erratic. Somwati’s response is matter of fact. The vagaries of the weather are woven into the rhythms of her everyday life. Villagers, and even bankers, concede that agriculture is a gamble for marginal farmers and sharecroppers, prone to fluctuations in money and the monsoon. Somwati’s ecological precarity gives her nothin g by way of an exception and she does not use it as a justification for her inability to return her loan.

A few days later I meet her in a field picking grain from the few rice crops still standing amid rows of rotting stalks. The water has receded, but our feet still sink into the damp soil. Somwati tells me she is currently paying off five microfinance loans. I remark she has more loans than the current regulation allows. She says her son, a house painter in Bangalore, fell sick; he contracted some ailment she cannot describe, and the arrears added up.

I came across many women like Somwati who were unable to repay their debts that year. The reasons they provided invariably drew on the exceptional — ailments, motorbike accidents, surgeries, a drunk husband who jumped off a roof, floods in Bangalore that stranded a migrant family; a tijori or safe that spontaneously combusted. Amplified or otherwise, the presentation of these exceptions was necessary, particularly to stave off the onslaught of moral judgement that often accompanied the procurement of debt or its default. Bank officers, loan agents, and upper caste landholding families routinely cast microfinance borrowers as uneducated, prone to excesses, living beyond their means, or simply incapable of managing their finances. In Somwati’s house, Raja told me, “Once these families get the money, they will sleep.” He pointed to a bed covered in mosquito net inside the house. “They won’t do any work until the money is finished.”

I never observed microfinance agents in this part of UP ask what businesses these loans were meant to facilitate. The forms usually stated gai-bhains or bakri (cows-buffalos or goats). It was the default selection. Loan officers understood that microfinance rarely kickstarted businesses or generated additional income among poorer families in these villages, and it freed them to be vocal in their judgements.

In Mumbai, financial analysts offered other reasons for what they called a “crisis” in the microfinance sector6. They came on news channels in 2024 and 2025 to report that loan borrowers in several states, including UP, were “overleveraged.”7 In other words, women had taken too many loans and were unable to pay back. When I met one of the analysts, he explained that some microfinance companies had raised large volumes of private and international capital and had been aggressive in their loan disbursements to communities to meet investor targets. Many had also increased interest rates and loan amounts in line with recent regulation. When the banking regulator in India put a temporary moratorium on some firms charging high interest rates, families who typically borrowed from one loan agency to pay back another lost their source of repayment. This resulted in a spate of defaults. In the second half of 2024, extreme heat was offered as another explanation. Some microfinance representatives said that heatwaves in parts of North India had resulted in loan agents abruptly quitting their jobs, resulting in inadequate collections.

Buried or overlooked among these narratives — which forefront the impact of extreme weather, misfortunes of borrowers, their supposed moral deficiencies, or the regulatory climate they encounter — is the unviability of debt itself. Microcredit, with high interest rates and extractive collection mechanisms is unable to resolve the everyday challenges of rural reproduction, much less produce socio-economic or ecological resilience. Yet debt continues to prevail as a sustainable solution for finance.

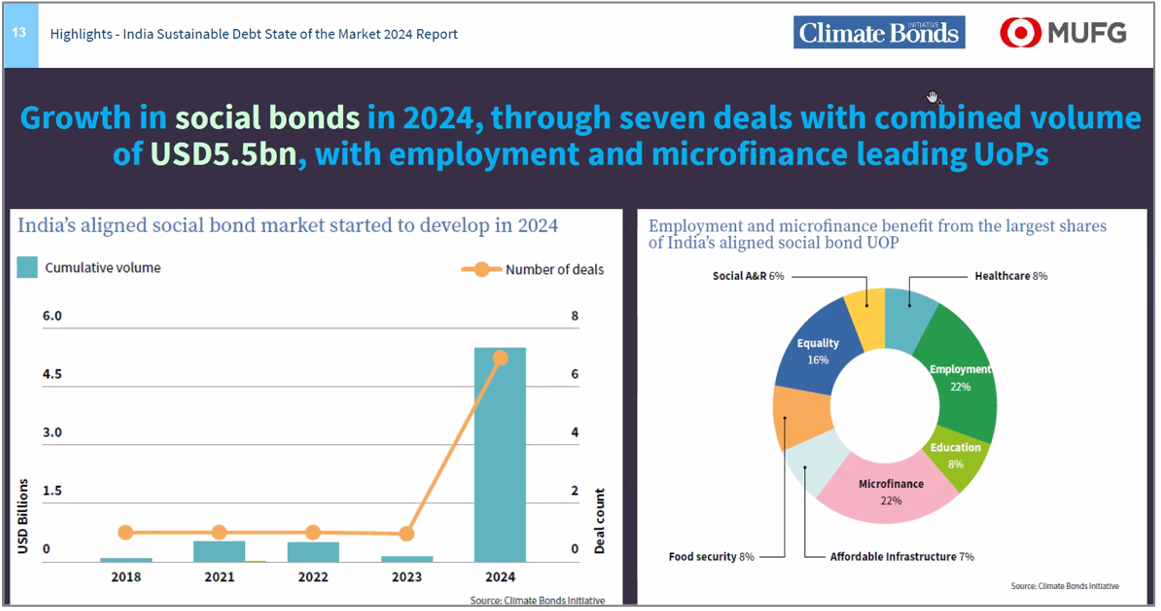

Consultants in India have begun labelling banks’ efforts at facilitating financial inclusion, mobile banking, and microfinance as debt that is “green” “social,” or enabling “A&R” (adaptation and resilience)8. This is an extension of the idea that the provision of formal finance to communities at the margins, if accessible and timely, is potentially sustainable because it can improve a family’s social capital and build their adaptive capacity. For financial institutions, efforts at tagging some types of finance as green has also opened new opportunities such as subsidised or concessional credit from international funders to meet their sustainable development, climate, and environmental, social and governance or ESG targets. Funders and investors in turn expect financial actors to measure and disseminate quantified metrics such as the number of peripheral bank accounts opened, women entrepreneurs created, emission reductions enabled, climate-smart initiatives financed etc.

Company sustainability reports are filled with upward trending graphs and photographs of men and women beside water structures and solar irrigation systems. These images and estimates belie the full picture: not all families access credit on the same terms, not all credit results in successful micro-businesses or climate proofed structures. Household indebtedness in many cases is cyclical and pervasive. Formal loans with their values and interest rates tagged to factors such as borrower income, asset ownership, and credit scores (not to mention other types of informal calculations), often reproduce class and caste hierarchies. Unsurprisingly, Dalit women like Somwati rarely qualify for collateral free, low interest bank loans that are state-subsidised and ostensibly designed for the marginal farmers and sharecroppers like her.9

The urban financial climate — produced by private and regulatory institutions across Mumbai, Delhi, and London — is representative of a particular metropolitan logic to governing climate finance. Organisations and regulatory bodies advocate just, sustainable, and equitable outcomes but co-opt practices that miss or simply ignore the unequal production of social mobility and resilience among communities in the peripheries.

Many financial actors I met in Delhi and London justified their approach to green lending by presenting anecdotes of men and women who had turned their lives around with the help of impact investments in e-rickshaws or microcredit in poultry farming in rural India. The Dalit families and marginal farmers I spent time with, however, seemed trapped in a cycle of debt. Their access to finance from microcredit, self-help groups, and informal loans did little to prop-up their income from agriculture and informal labour. Rather, their service of debt subsumed the latter.

Collective efforts by some nation-states have rightfully served to reiterate the burden of sovereign debt to poor nations in a climate-impacted world. Yet, such narratives don’t crystallise at the scale of communities where household debt is more individualising. For many families, ecological vulnerability is not a one-off crisis, but a slow process of erosion, tied to wider patterns of socio-economic precarity, and incompatible with the short repayment cycles that finance demands. Groups created by microfinance, that could function as sites of solidarity and claim making among women, have instead served to protect the interests of finance. Moreover, in India, when one-off politically motivated loan waivers are announced by states, they preclude debt erasure from microfinance. It’s on these unequal terms that the edifice of private adaptation finance is being constructed. Despite calls for building a just and resilient climate transition then, the newfound governance of green finance remains disconnected from how communities at the microscale negotiate financial and ecological precarity.

Gross Domestic Product; Mia Motley, COP27 World Leaders Summit, 2023

Decoding the future: Global Financial Architecture reforms. UN Sustainable Development Group, 2024.

Big Plans for a new generation of country platforms. ODIGlobal, 2025

Laura Bear, Navigating Austerity: Currents of Debt Along a South Asian River. 2015.

Final Draft Bridgetown Initiative 3.0

Economic Times, April 2025

CNBC TV18, September 2024

India Sustainable Debt State of the Market Report, Climate Bonds Initiative 2025

Joint liability groups, Punjab National Bank; Sohini Kar, 2018

Time of India, October 2024

1 Gross Domestic Product; Mia Motley, COP27 World Leaders Summit, 2023

2 Decoding the future: Global Financial Architecture reforms. UN Sustainable Development Group, 2024.

3 Big Plans for a new generation of country platforms. ODIGlobal, 2025

4 Laura Bear, Navigating Austerity: Currents of Debt Along a South Asian River. 2015.

5 Final Draft Bridgetown Initiative 3.0

6 Economic Times, April 2025

7 CNBC TV18, September 2024

8 India Sustainable Debt State of the Market Report, Climate Bonds Initiative 2025

9 State Bank of India, Pradhan Mantri Mudra Yojna