The (under)ground or (sub)terranean environment is a thick, complex, three-dimensional space of ‘nothing but change’ whose utility is essential to sustaining urban life above it. Living with these grounds is living in conditions of unstable hydrogeological emergence. Such a condition is experienced in Chennai, South India, where the everyday abstraction (extraction) of groundwater is relied upon for around one third of the city’s water supply.

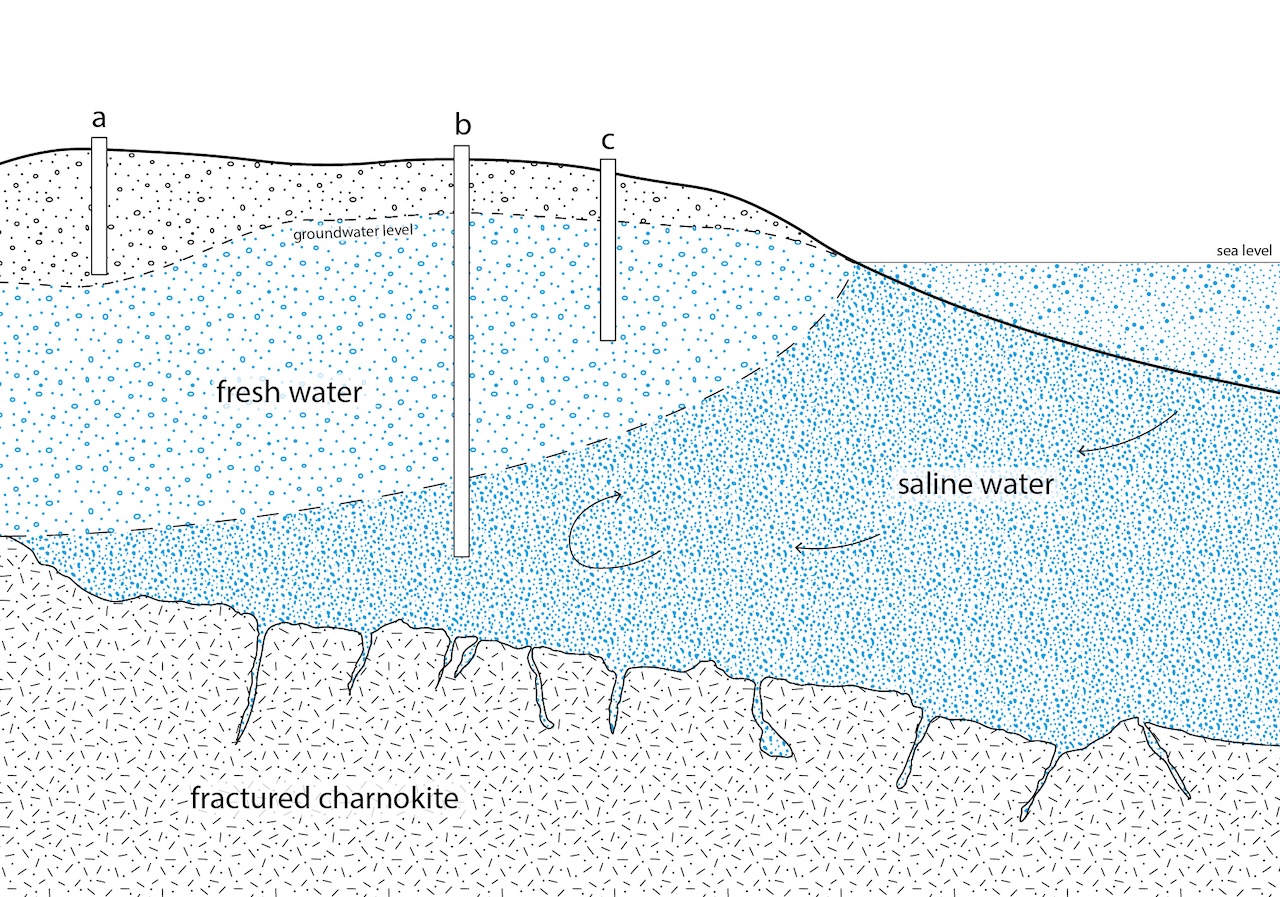

Groundwater is a persistent presence in narratives of the lived-in city: both as a volumetric resource, ‘the river flowing just below the surface’, which needs to be cared for and replenished by means of recharge structures; and as a stratified zone through which basements and tunnels are built; and as a diverse ecology of minerals and microorganisms modified both by seawater intrusion and anthropogenic contaminants. Groundwater appears in narratives of both drought and flooding as waves of the underground monsoon.

I first came to know groundwater as a substance that might enable me to write about the entanglements of monsoonal weather and rapid urban change in Chennai, and this project proposes thinking with groundwater from Chennai as a mode of engagement with the complex intra-active relations of changing city and changing climate. It looks at the multiple, specific, and contradictory ways of knowing groundwater in Chennai, South India—ways in which the materiality of groundwater is understood and intervened in—where groundwater is understood as being composed of manifold materials, processes, and representational practices. If ‘the question of how to live in a world shaped by relational entanglements and feedbacks is the problematic of contemporary Anthropocene thinking’ then groundwater, I propose, is a useful figure with which to think through some of these relational entanglements and feedbacks (Chandler and Pugh 2021).

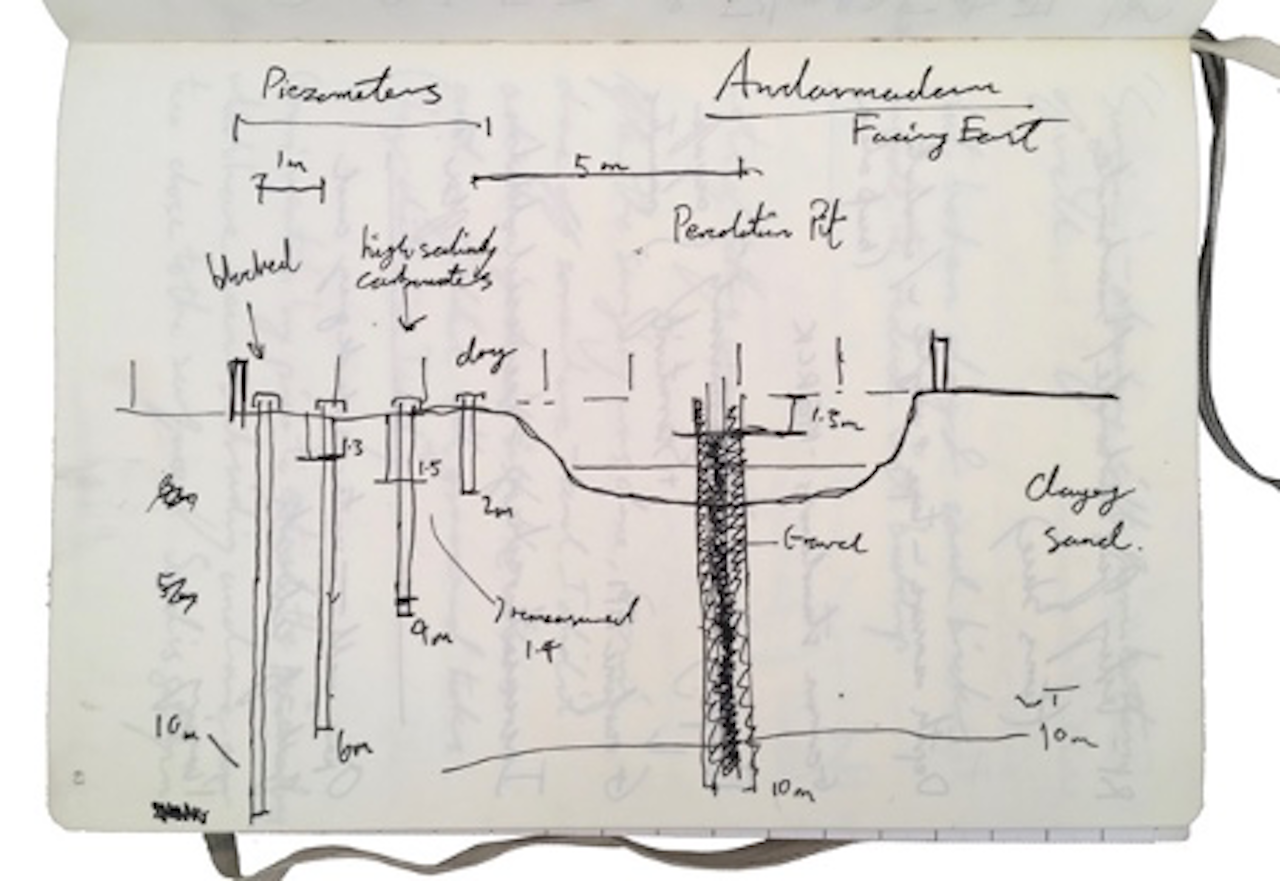

First, I ask what groundwater is, and how I might approach it. Through a series of case studies, I develop a methodology for researching groundwater, confronting the problem of how to research and write something that I cannot access. This means talking to different people who access groundwater in different ways, assembling multiple and contradictory accounts in a way that acknowledges and keeps hold of the intra-active tension between materiality and representation. My means of access are the multiple ways that different people, professions, and institutions get at groundwater, and the project evolved through interviews, shadowing, and following the work of others. Alongside this, I developed my own representational practices for engaging with groundwater, as further means of grasping at something always at a distance.

Through this I ask, what knowledges exist? How are these different knowledges co-produced, and how are they enacted or re-inscribed through scientific, professional, and everyday practices? The format is processual and iterative: I do not set out to clean up the steps by which research methods, analysis, and theory co-evolve. Each case study is an experiment with ways of knowing groundwater.

Throughout these different points of view, it is impossible to say quite what groundwater is, other than a set of relations that move in and between urban climates—a socionatural, hybrid condition, inseparable into constituent parts. Groundwater appears and is drawn into focus as a register which can bring together accounts of such diverse phenomena as alluvial geomorphology, social inequality, municipal engineering, and more. The closer I look at it, the less it appears as a discernible, material ‘thing’: instead I begin to make sense of groundwater as a relational substance, one which is not a background to the city’s ongoing reproduction, but is both substantially altered by and co-constitutive it. Groundwater moves through the city both literally and conceptually as a changing set of relations which shift and need to be followed. Different positions will yield different sets of characters, as certain conceptual frames and knowledge practices bring different aspects of it into view. As such, a transdisciplinary reading of the city through groundwater brings to the fore conditions of relationality (such as leaking, swelling, and cracking) through which urban climates are reproduced.

In commercial kitchens, for example, the fans and exhausts are in constant motion to keep the space ventilated. So much so, that the staff often step outside in the heat to get a breather and cool off. Within the kitchen, the workers have set up a “break corner” with a pedestal fan. The fan has a considerably lower volume as compared to the exhaust, creating space between the hot kitchen and the cooling area.

Chandler, D., and Pugh, J., (2021). “Anthropocene Islands: There Are Only Islands after the End of the World,” Dialogues in Human Geography, 2.

Powis, A., (2020). “An Excess of Thought, or the Thinking Materials of Research.” Hyphen Journal 2. http://hy-phen.space/journal/issue-2/powis-an-excess-of-thought/

Powis, A., (2020). “Acts of Drawing Something You Cannot See.” In Monsoon [+ Other] Grounds, edited by Lindsay Bremner and John Cook, 89–95. Monsoon Assemblages, http://www.monass.org/writing/

Powis, A., (2021). “The Relational Materiality of Groundwater.” GeoHumanities, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/2373566X.2021.1925574

Powis, A., (2021). “Thinking with Groundwater from Chennai.” In Monsoon As Method: A Book by Monsoon Assemblages, edited by Lindsay Bremner. Barcelona: Actar. https://www.schulerbooks.com/book/9781948765787