In the peri-urban settlements on the outskirts of Karachi, summers are becoming more unbearable as the intensity and duration of summers are rising each passing year. The families have no choice but to live in tightly spaced abodes, which feel like ovens during daytime with no major respite at night and the frequent power outages further adds to the agony. The poor living and socio-economic environment pose added threat to their health, with children and the elderly, particularly at risk.

The streets are narrow and winding, flanked by compact houses constructed with cement blocks, tin sheets, and whatever materials residents could afford or salvage. Many of the homes are single-room units, expanded vertically over time without formal design or engineering support. These structures sit close together, leaving little room for airflow or light to pass through. Most homes lack functional windows or ventilators, and privacy concerns often force even existing openings to remain shut. During summer, heat builds up inside these spaces absorbed by concrete and tin and lingers well into the night. Frequent power outages only worsen the discomfort, making fans and cooling devices unreliable, if not completely unusable. There is no green cover, no trees, no parks, no public spaces, making the areas particularly vulnerable to the urban heat island effect. There are examples of institutes and individuals who are exploring how rapid urbanization has affected the life of its inhabitants and also exploring ways to mitigate those. One prominent example is the work of Arif Hasan on urban planning, architecture, and community development in Karachi and his influential role in low-income housing solutions (like the Orangi Pilot Project).

Despite these conditions, the community shows remarkable adaptability. Makeshift shading, elevated sleeping spaces, and improvised cooling methods are common, yet these are stopgap solutions. The structures themselves amplify heat, and the surrounding environment offers little reprieve. In this context, heat is not only a discomfort it is a daily hazard, shaped by the built environment and deepened by systemic neglect.

The study is being conducted in the Korangi district of Karachi. The community is constituted primarily by working-class families who have migrated from different parts of the country and engaged in daily-wage labor, small-scale manufacturing, and informal vending. The Structural Heat Adaptation and Education in Urban Setting (SHAPeS) initiative, led by the Institute for Global Health and Development at Aga Khan University in collaboration with the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and University College London, was developed to address the growing issue of increased heat stress, and to explore feasible, affordable, and practical solutions to make the existing structures cooler and more livable for vulnerable communities. Rather than importing high-tech solutions and focusing on building new climate friendly structures, the SHAPeS team focused on ideas that were driven by indigenous and scientific knowledge, and which were acceptable and plausible in the context that we were striving to work in.

The foremost step was engaging with the residents. Engineers, architects and researchers visited these areas, discussed issues that residents were encountering, and documented how people were coping with the extreme heat. Many described how kitchens become unbearably hot during the day, especially troublesome for pregnant women and disturbed their sleep during night. The children and elderly often fell sick due to the constant exposure to high temperatures.

These active engagements with the community ensured that their lived experiences helped shape the direction of the built interventions. From the outset, the community was treated as a partner, not a subject which helped overcome the initial resistance. Residents also shared their coping strategies and challenged our initial designs with practical insights, suggesting where ventilation was needed or how shading could be more useful. Their feedback refined our plans in ways that technical knowledge alone could not. During implementation, the collaboration deepened, as some families offered their homes for trials; others helped monitor installations or assisted with material handling. Engineers and architects remained on site, engaging continuously with households. At the same time, medical researchers tracked how these changes could influence health and thermal comfort, grounding the interventions in medical evidence.

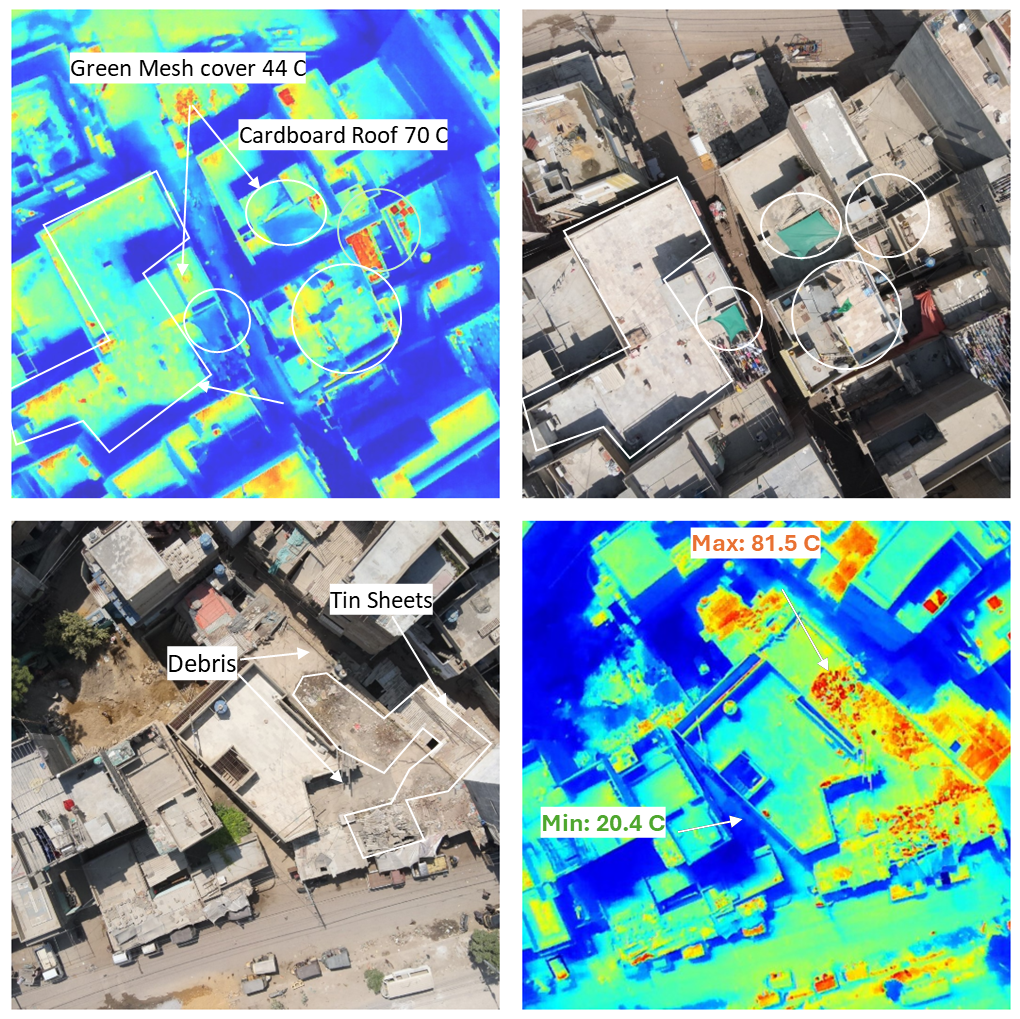

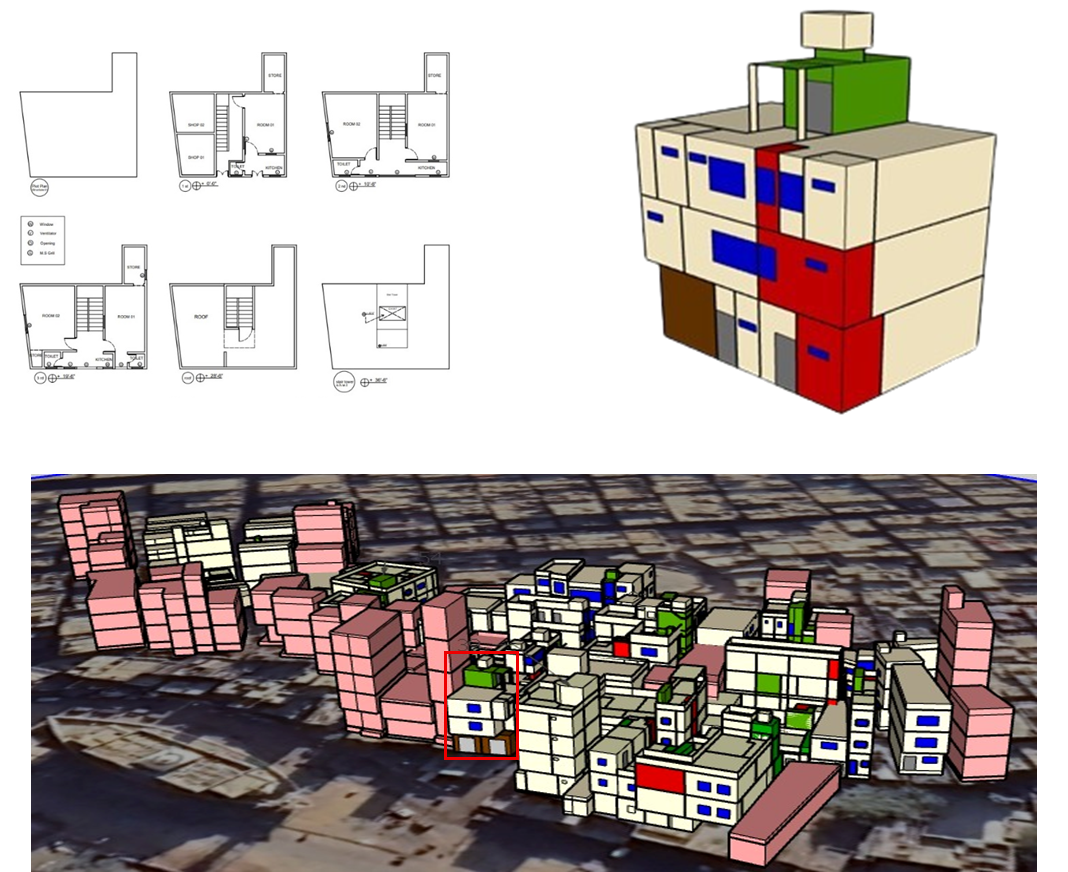

To understand heat patterns through a quantitative metric, the team collected real-time data using standardized devices, including drone-based thermal imaging to map the hottest rooftops and outdoor spaces (Fig-1) and i-Buttons for indoor and ambient temperature. These measurements provided a clear picture of the temperature patterns throughout the day and night, and how various building materials, design and topography contributed to the increased temperatures. Digital 2D and 3D models (Fig-2) were then created for each structure which helped the team understand the role of building material (tin), design and orientation in trapping and retaining heat and showed how simple coverings (green net) over the roof can help reduce surface temperatures.

We held a series of consultations where the findings from both qualitative interviews and quantitative measurements were discussed with a wide group of stakeholders, including architects, engineers, urban planners, social scientists, and most importantly, local community members. This multidisciplinary process ensured that technical knowledge was balanced with lived experience. Residents, especially women and elderly people, shared their priorities around privacy, cost, and ease of maintenance, while experts helped evaluate thermal performance and structural feasibility of different materials. A range of possible interventions were finalized.

These included solar reflective paint on rooftops, traditional lime wash on walls and roofs, lightweight insulation sheets (known as Polyurethane Thermopore), behind internal walls, roof shade materials (light weight HDPE nets and canvas over a bamboo structure), window shading and improving the ventilation within the living spaces (creating windows and ventilators).

In some structures, fans with batteries powered by solar panels were installed to ensure continuous power and air circulation. We were cognizant that the solutions had to be affordable, locally available, and such that residents could maintain and replicate themselves or with minimal support. We began by reviewing options through the lens of passive cooling materials that could reflect, block, or slow down heat. We tested these in situ to assess their effectiveness in tightly packed, poorly ventilated structures. Numerous solar reflective paint brands were tested, traditional lime wash was tested and these proved both practical and cost-effective, offering noticeable temperature reduction when applied to walls and roofs. Polyurethane thermopore sheets were lightweight and easy to install and hence, were selected for wall insulation. For roof shading, we opted for bamboo frames covered with HDPE mesh or canvas, a combination that was durable, breathable, and visually acceptable to the community.

Beyond individual household structures, we considered heat effects at the community level through street shading provided through trees and large nets made from high-density polyethylene.

Construction on-site brought its own set of challenges. The narrow alleys meant materials had to be carried by hand. Each home was different, requiring custom fitting of insulation or structural adjustments to install ventilators. Coordination with local laborers was essential not only for efficiency but to build trust within the community. Work was done in phases, often adjusted based on daily household routines to respect privacy and minimize disruption. Through this hands-on, adaptive process, construction became more than just technical execution, and was a shared effort, rooted in listening, learning, and building together. The final interventions were shaped and adjusted in ways acceptable to residents.

We collected post intervention data, which suggested that structural modifications helped improve overall living conditions by reducing indoor temperatures, providing some respite from intense heat during peak hours, thus improving quality of life. Some notable differences were seen in structures where polyurethane thermopore insulation and reflective roof paint were applied in combination, lime wash helped reduce temperatures, and roof shading helped reduce the indoor temperatures during peak hours. The continuous energy and enhanced ventilation through added windows allowed air circulation, which reduced temperatures and significantly improved heat perceptions. Together, these passive cooling methods offered a noticeable improvement in indoor comfort across multiple structures and helped improve the quality of life of its inhabitants as one resident highlighted that “these interventions are not only lowering the indoor temperatures but improving their quality of life.”

Residents described the changes in tangible ways; families reported finally being able to sleep through the night without waking up drenched in sweat, mothers shared that children were falling sick less often, while elderly residents noted that sitting indoors no longer felt as suffocated during the afternoons. Some even began to use their living spaces more actively as women could cook with less discomfort, and children could study indoors rather than moving outdoors in search of cooler space. One resident remarked that with the shaded street nets, “the gali (street) feels alive again, people come out and sit together.” These testimonies underscored how comfort was not only about lower temperatures, but also about reclaiming health, rest, and social life.

SHAPeS showed the significance of multi-scalar approaches to heat mitigation informed by design and technologies rooted in the realities of daily life. Crucially, recognizing the microclimates that exist within homes, streets, and neighborhoods is essential for shaping broader urban-scale heat management policies. Without grounding citywide strategies in lived, localized experiences, urban planning risks overlooking contexts where heat is most acutely felt.

After the pilot testing of these interventions, we are now embarking on a full-scale implementation which would be tested formally through a randomized controlled trial with ten clusters (70 households) each in the intervention and control arm. The impact of these interventions would be tested not only on the change in indoor environment but also on the health of individuals, especially to the most vulnerable. The results of this trial will help generate evidence which can be used locally and internally for advocacy for scale up. The interventions proposed are grounded to the context, use a mix of local and technical knowledge, have a low-cost plausible approach and involve active community engagement which was reflected in around 25% of the financial contribution from the community itself. The collaborative approach shows how communities can self-help and how it can help address the system neglect that these communities have been enduring for a long time.

SHAPeS shows how an active community engagement with a collaborative process where science meets local wisdom, and solutions shaped together can empower communities and offer sustainable change which not only improves the environment but also provides comfort, dignity, and safety.

The project is funded by the Wellcome trust, and the updates would be provided on https://www.aku.edu/ighd/research-programmes/Pages/assessing-heat-adaptation.aspx