“Kanak katne ka ek mahina hamare liye bahut aukha ho jata hai, pure gaon me har jagah sirf tudi hoti hai (The month of wheat harvest gets very difficult for us, as there is wheat straw everywhere)”, said a woman from Lehra Mohabbat village near Bathinda city in Punjab, India, when asked about the local aab-o-hawa during the summer season. The wheat harvesting season worsens surrounding aab-o-hawa in Bathinda resulting in the social, environmental and physical discomfort in the everyday life of village dwellers.

Broadly speaking, climate is understood as long term weather conditions in particular geographies. With the growing global focus on climate change, like COP29 in Baku, countries are racing toward net-zero targets. India’s 2070 net-zero pledge centers on emissions and data. While these macro goals matter, policy emphasis has largely been on targets, emissions and large data sets rather than the lived and situated experiences of the climate.

Shifting the focus from carbon to air, this case study thus develops the vocabularies and articulations of the local climate — specifically aab-o-hawa in Lehra Mohabbat during the wheat harvest season. It explores two kinds of weather extremes — abundant tudi as a pollutant and high temperatures — both of which affect air and the weather. From tibbe (sand dunes) to tudi (hay prepared after harvesting wheat straw), we trace how land, life, and labour have been reshaped by extraction, irrigation, and aspiration, where wheat isn’t just grown and consumed but also breathed.

Rather than reducing climate to abstractions, we understand it in the ways it is experienced sensorially via weather and aabo-hawa. Here, air becomes a medium: “Hawa se tudi ud ke aati hai”; it blends with smoke: “Hawa mein dhuan hota hai jab kanak jalti hai”; and it’s felt in the body: “Hawa ka bhari hona.” This essay builds an understanding of weather in confluence with air quality of the village and how atmospheric disturbances shape local weather.

Bathinda, once part of the Lakhi Jungle, was a semi-arid landscape of sand dunes, colloquially known as tibbe wali dharti. Located in the Malwa region of Punjab, the region’s developmental path has irreversibly transformed the environment. This change is linked to the way land signifies a different and instrumental relationship to modern producers and consumers (Dale, 1997). Punjab Land Records reflect this change, reclassifying dense forest once labeled banjar (wasteland) into Chahi (tubewell-irrigated) and Nehri (canal-irrigated) farmland (Punjab Land Records Society, 2004). This transition from forest and desert to agricultural and industrial uses is central to understanding today’s climate extremes in Punjab.

Tibbe or sand dunes are an identity marker of the region’s past. While they have largely disappeared, traces reappear every now and then, both in space and cultural memory. The popular slain musician Sidhu Moosewala, who hailed from a similar geography to Bathinda, titled one of his songs Tibbeyan Da Putt (Son of the Dunes), evoking this heritage.

Though often seen as obstacles to development, tibbe are still valued by locals for their ecological role, as a village functionary described them as “lungs of the earth,” regulating temperature through their porous structure. The tibbe are posed as a possible explanation why Bathinda was chosen for Punjab’s first thermal power plant in the 1960s and further industrial expansion (Bhatia, 2013).

Despite industrial expansion, Bathinda remains primarily agrarian. During the Green Revolution in the 1960s, the agricultural landscape shifted from traditional practices, such as canal irrigation, crop rotation, manual and animal-based harvesting, and mixed farming to input intensive methods including High Yielding Variety (HYV) seeds, chemical fertilizers and pesticides, tubewells, and mechanised equipments like tractors and super seeders. This ended the country’s famine, but also deepened Punjab’s agrarian crisis. “Punjab khilate khilate khud khaali ho gaya,” (Punjab starved itself while feeding the country) said a farmer from Lehra Mohabbat, describing how paddy replaced cotton, altering cropping patterns, varieties, and timings (Sinha, 2022). Subsequently, the Punjab Preservation of Subsoil Water Act of 2009 further reshaped the agricultural practices to conserve groundwater. The Act mandates paddy sowing alignment with monsoons, which makes winter wheat crop then a time-restricted event, with a narrow window between paddy harvest and wheat sowing. Wheat must be harvested in April to allow timely paddy sowing by June. Any delay forces farmers to adjust sowing, harvesting, storage and land preparation.

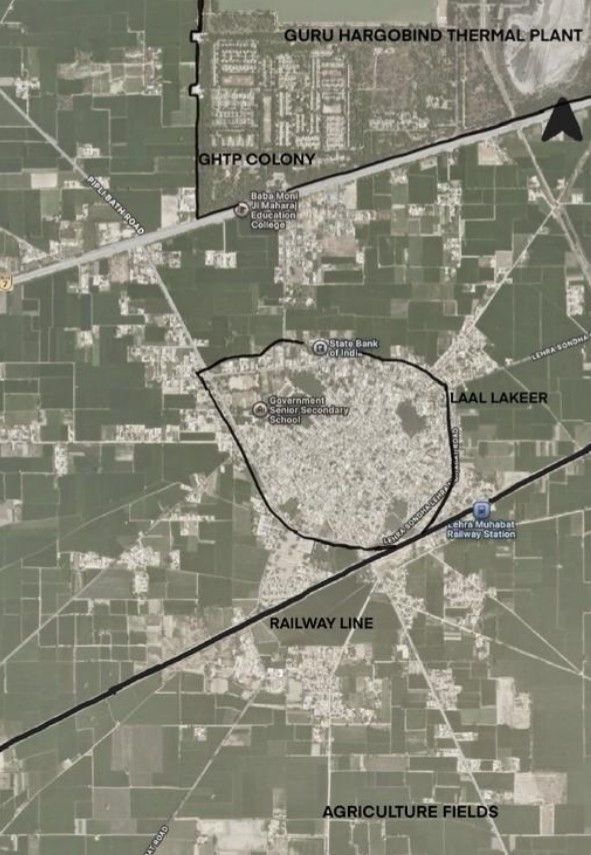

This case study looks closely at two resulting aspects of harvest season in Punjab: rising temperatures and the material presence of tudi. We examine the harvesting season of wheat in a Lehra Mohabbat village, situated in the north-eastern part of Bathinda in Punjab. While paddy stubble dominates air quality debates in the Indo-gangetic plains in Nov-Dec, wheat stubble puts people in weathering extremes too, disrupting the daily rhythms of villages, completely transforming the everyday life of village dwellers.

Harvest depends on weather conditions. Rising temperatures, especially during the grain-filling stage, speed up crop maturation, reducing grain weight and yield. In 2022, early heat pushed the wheat harvest to early March (Kajal, 2022), while in contrast, 2025 saw a delayed harvest extending beyond mid-April, highlighting the growing unpredictability driven by climate change (Bedi et al., 2024). This is also reflected in a report published by the Indian Council of Agricultural Research which states that Bathinda is in a high climate risk category with a history of droughts and future hazard of increase in temperature (ICAR, 2019).

This shifting wheat cycle — driven by late winters, delayed paddy procurement, and fertilizer shortages pushes harvest into peak summer (Mander, 2024), leading to risk of standing wheat crop fire accidents. Heat, faulty wiring, sparks in harvesters and tractors, lit cigarettes can ignite dry fields and even andheri (wind storms) can cause fires in the fields. Smoke rising from fields is a common sight during the summers and regular fire alerts emanate from the gurudwaras. People rush with water and soil while digging fields to stop the fires from spreading. In the absence of any insurance policy, compensation amounts also fail to cover adequately for the farmers’ losses (Kamal, 2025).

As sand dunes were levelled and water flowed in canals, once ‘banjar’ / ‘barani’ (land with no water) land began yielding abundant food. Bathinda, among Punjab’s top wheat-producing districts, harvested 182.58 lakh tonnes in 2018–19 (Nibber, 2024). This abundant production has resulted in a new kind of unmanageable excess in the form of wheat straw or tudi. After the wheat is harvested using a super seeder, about 6-8 inch long thin stalks remain embedded in the ground from each wheat straw called tangad. These are then converted into tudi using straw reapers and used as fodder for animals, binding agent in buildings with cow dung, and insulation agent to keep things cool.

In Lehra Mohabbat and other villages of north India, wheat stubble, like paddy, is also burnt without making fodder, suspending particulate matter and smoke into the atmosphere, making black ash particles or rakh a common sight in the villages. Parwinder ji, a village resident told us:

“Tudi is so fine that if windows are open, it settles on clothes and around the house, causing breathing trouble. It’s impossible to clean. Labourers from oppressed castes or other states load and unload it, otherwise, it’s just burnt in the fields. Even when used, the leftover stubble is still burned.”

She also highlighted that declining livestock has reduced tudi’s demand. Children complained to us about itchy throats and irritation in eyes, with the worst effects felt by Dalit and Mazhabi Sikh families living near the fields, especially south of the railway line, where exposure to smoke, straw, and pesticides fumes is the highest.

In the two months following the harvest of wheat, the air of the village is filled with powdered wheat straw. This is stirred up in the air with every passing trolley and truck causing pulmonary distress and discomfort. Tudi is also a leading cause of clogging open drains. The life of the village is therefore disrupted by this unwieldy companion to farming.

Tudi, its processing, storage and overall presence in the air is deeply entangled with the social life of the village. Farmers coordinate harvest schedules to help each other process it, with women largely managing its loading, unloading, and storage in homes and stables. Several of our interviews in the Lehra Mohabbat village were in fact cut short because our interlocutors had to rush to the farm to process wheat straw. Life in the village is re-calibrated to meet the demands of the harvesting season. Children in the village are stopped from playing outside in the streets because of the sheer number of trolleys and tractors carrying processed tudi from fields to homes.

Where sand dunes once cooled the earth, burning straw now heats and pollutes the air. In Lehra Mohabbat, weather extremes are not abstract — they are shaped at the intersection of agricultural systems, land use, and modernizing geographies, and experienced in the everyday. Temperature shifts aren’t just degrees on a scale, but lived culturally through festivals like Baisakhi, now out of sync with the harvest (Gill, 2025). Then, temperature difference and its effects are lived. The brunt is borne by the farmer whose crops catch fire. Additionally, tarakki [progress] in agricultural practices produces a new kind of extreme. A small particulate matter disrupts the air and life of the village. Weather then, doesn’t remain contained to an idea of hot/cold weather, or four seasons. It is also a two-month period where air is disrupted and the weather is changed. Extremities are felt when wheat fields catch fire or tudi gets deposited in the lungs. Joshi (2021) has argued that postcolonial ecology must shift its focus away from Western Enlightenment ideals, and call into question long-held binary distinctions between local/indigenous relationship to land and modernisation/development of land. A postcolonial approach to development must disrupt this binary by integrating local and embodied experiences to shape development strategies and modern technologies. The case of Bathinda clearly shows the flip side of development when the relationship between people and land is ignored. The idea of progress/development has continually been equated with yield in agriculture ignoring the fertility of land and health of its residents. One must not come at the cost of another. Instead, tarakki must be rooted to build a better relationship between land and people, not land and capital. As we talk about climate change, Lehra Mohabbat is a living example of a crisis well defined by people’s embodied and lived experiences.

Note: Fieldwork photographs by authors

Kajal, K. (2022, June 8). “Heatwave takes a toll on north India’s wheat yield.” Mongabay-India.

Bedi, A., Burrell, J., & Flores, A. (2024, July 20). “Commentary: Harvesting uncertainty: navigating punjab’s climate crisis.” Stanford Economic Review.

Bhatia, A. K. (2013). Ground water information booklet Bathinda district, Punjab. Central Ground Water Board, Ministry of Water Resources Government of India.

Commission for Air Quality Management in National Capital Region and Adjoining Areas. (2021, June 10). Providing an effective framework, action plan and steps to be taken to tackle the problem of stubble burning (Direction No. 10).

Dale, V. H. (1997). “The relationship between land-use change and climate change.” Ecological Applications, 7(3), 753–769.

Gill, M. S. (2025, April 13). “No longer in sync with crop harvest, Baisakhi retains its joie de vivre.” The Tribune.

Joshi, S. (2021). Climate Change Justice and Global Resource Commons: Local and Global Postcolonial Political Ecologies (1st ed.). Routledge.

Kamal, N. (2025, April 22). “Flames amid wheat harvesting: 2,230 acres of crop lost in Punjab over a decade.” The Times of India.

Mander, M. (2024, December 4). “Late wheat sowing may hit yield, farmers worried.” The Tribune.

Nibber, G. S. (2024, April 16). “Punjab readies for glut of wheat crop after slow start to procurement.” Hindustan Times.

Press Information Bureau, Government of India. (2024, November 25). “Parliament question: Air pollution caused by stubble burning” [Press release].

Punjab Land Records Society. (2004, June 8). Punjab Land Record Manual.

Rao, C. A. R., Raju, B. M. K., Islam, A., Rao, A. V. M. S., Rao, K. V., Chary, G. R., Kumar, R. N., Prabhakar, M., Reddy, K. S., Bhaskar, S., & Chaudhari, S. K. (2019). Risk and Vulnerability Assessment of Indian Agriculture to Climate Change. ICAR-Central Research Institute for Dryland Agriculture.

Role of district administration | district bathinda, government of punjab | India. (n.d.). Retrieved June 25, 2025,

Shreya Sinha, “From Cotton to Paddy: Political Crops in the Indian Punjab,” Geoforum 130 (March 2022): 146–54.

Anon (2023, March 8). “We are unnecessarily being targeted, defamed for Delhi air pollution, say Punjab farmers.”The Hindu.