Rapid urbanization across South Asian megacities is accelerating environmental crises and the concurrent decline of urban nature spaces. Lahore, Pakistan’s second-largest city, epitomizes this compounding effect. Here, residents are subjected to a cyclical environmental crisis throughout the year: extremely high summer temperatures reaching up to 48°C; catastrophic monsoon urban flooding recording up to 350mm of rain in just few hours; and hazardous winter smog where Air Quality Index (AQI) levels have spiked to 954.

Yet, the green infrastructure essential for mitigating these climatic upheavals is rapidly reducing. Lahore, once known as a ‘city of gardens,’ since 1990 has lost about a third of its green footprint, shrinking from 1,205 to 846 square kilometers (Azhar et al., 2024). Currently, green space availability is 7.3 square meters per inhabitant, falling short of the WHO's minimum standard of 9 square meters (Shoaib et al., 2022). This reduction in green footprint is not only an ecological loss but is also linked to socio-spatial and environmental inequities, where experiences of urban nature differ across various parts of the cities (Anguelovski and Connolly, 2024). Today, spaces of urban nature are not only scarce, but also unevenly distributed (Alam and Shirazi, 2014) and frequently compromised by infrastructure development. While formal green spaces tend to be meticulously maintained, commodified, and contained within elite enclaves, opportunities for marginalized citizens to interact with urban nature are considerably limited. Consequently, they rely on informal and liminal urban nature spaces such as the banks of Lahore Canal. By examining the Lahore Canal through the lens of everyday adaptation, this case reframes it as a contested yet essential urban commons, shaped and sustained by citizens as a response to Lahore’s rising extreme weather conditions and infrastructural developments.

The Lahore Canal, a green, blue, and now predominantly grey corridor, epitomizes the tension between the development of transport infrastructure and the need for preservation of liminal urban nature spaces. In this context, liminality refers to the canal’s ambivalent landscape. It is a threshold space where rigid road infrastructure overlaps with fluid ecological processes. Characterized by its dual nature, the liminal urban nature spaces along the banks of canal are neither fully wild nor completely manicured by human agency — these spaces are technically state-controlled yet they function as interstitial green space outside of formal park frameworks, thereby allowing for informal public interaction with urban nature spaces along the canal.

The Lahore canal is a thirty-kilometer corridor which runs from northeast to southwest, traversing through both low-income, high-density and high-income, low-density neighborhoods. In affluent neighborhoods, the banks are defined by a 'curated nature,' featuring patches of seasonal flower beds. Here, urban nature serves primarily as a visual amenity for transient leisure; access is often controlled to preserve these highly maintained landscapes, resulting in passive human-nature interaction. This stands in sharp contrast to the densely populated neighborhoods along the canal, such as Nabipura, Fateh Garh, and Dharmpura. Here, the liminal green spaces along the canal serve as a vernacular climate infrastructure where every day urban life and ecological processes are interconnected: residents find respite from congested living conditions; every evening, older men gather under the shade of a few remaining old heritage trees (Sheesham, Neem, or Banyan) to play card games; children play along dusty and poorly maintained green patches; younger adults seek relief from Lahore’s scorching heat by swimming in the canal’s murky water. As one resident told me during the field work, “puray shehar mai humaray liye aisi thandak kahin nahi milti” (in the entire city, we can't find such a cool place of respite).These localized practices and engagements show how the canal bank transforms from mere green, blue, or grey infrastructure into everyday climate infrastructure that enables residents to weather the everyday crisis of heat and urban congestion.

The canal bank as an urban common becomes even more pronounced when it responds to the specific, localized needs of the community. Near Fateh Garh area, during the summer month of Ramadan, I observed that a group of young men leveling a patch of ground along the green corridor of canal, supervised by older men sitting nearby. Upon inquiry, they explained that their local mosque was too small to accommodate the entire community for the upcoming Eid prayer. Through their social agency, residents temporarily reconfigure the use, form, and meaning of this liminal green space into an Eid Gah (an open-air prayer ground), a site of profound cultural and religious significance. All of this collective action was a response to the lack of provision of essential urban infrastructure.

The interaction with urban nature spaces along canal is also deeply rooted in the survival apparatus of social-ecological consciousness. This became evident when a 100-year-old man was found living along the canal, under a banyan tree. For him, this was not just a green space but a refuge, essential to his existence. In an act of profound care, and with extremely limited resources he planted over a hundred trees, a testament to individual agency resisting the dominant state-led interventions that continuously reduce the city's green fabric. Such co-production of ecologies of care frames urban nature spaces along canal as lived climate infrastructure shaped by affective attachment.

Near the Jallo Park area, a widened section of the canal bank serves as a popular picnic spot for families. This section of canal bank is less than five hundred meters from a well-known private water park (Sozo Water Park), yet it thrives as a gathering space for low-income residents. One father explained his choice: “is mehangai mai hum apnay bachon ko yaha isi liye le keh atay hain keun ker ye muft tafreeh hai, sath hee sozo water park hai magar wahan ki ticket hee 1000 rupee hai” (in this inflation, we bring our children here because it is free entertainment; the Sozo Water Park is nearby, but its entry fee is 1000 Rupees). This simple act of choosing the canal bank over a commodified alternative underscores its role as accessible climate infrastructure for low-income families, where leisure and respite from heat remain basic needs rather than a commodity.

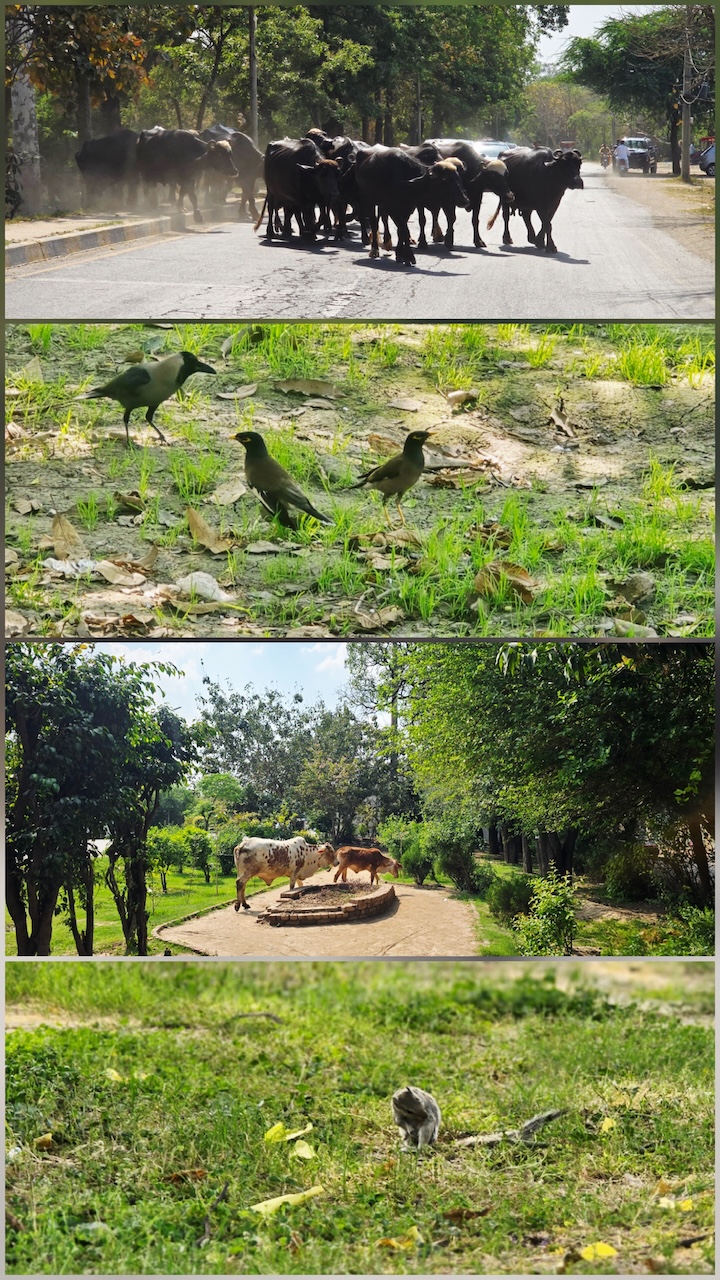

The canal not only sustains human-nature interaction, but is also an important site for non-human coexistence. As rapid urbanization and climate change deplete Lahore’s wider biodiversity, urban nature along the canal banks forms a unique ecosystem where: spontaneous vegetation along its banks creates conditions that enable various species to thrive, such linear ecological corridors in urban areas facilitate the species dispersal and gene flow of flora and fauna (Riley et al., 2014); amphibians and insects find vital food supply and conditions for reproduction and pollination; remaining native trees serve as a necessary refuge for birds species otherwise displaced by the city; even domestic livestock are brought to the canal’s murky water to fight against the extreme urban heat of Lahore. Furthermore, the canal supports Lahore’s broader green infrastructure through the circulation of bhal (nutrient-rich silt). These multi-species, multi-layered interactions occurring within the dense urban fabric, render the Lahore canal an emblematic site of coexistence and consolidate its role as shared climate infrastructure, where social-ecological assemblages form a fragile yet functioning ecosystem for the city.

These cyclical interactions are in direct conflict with the city's relentless march towards modernity, an agenda aimed at Lahore, like other cities, as a ‘world-class city’ (Harris, 2013), which prioritizes vehicular movement and planned development over social-ecological experiences in urban areas. The infrastructural interventions at canal road represent this car-centric planning approach. Officially, these interventions were justified as necessary to ease traffic congestion. However, critics from the Lahore Bachao Tehreek (Save Lahore Movement) argue that this intervention was based on miscalculation. The construction of underpasses, intended to ease congestion, actually generated more traffic, a phenomenon known as ‘induced demand’ (Cervero, 2009). In practice, what was framed as an adaptation to smoothen the flow of vehicular traffic, has become a form of maladaptation for communities inhabiting the urban nature spaces along the canal, intensifying their exposure to heat, pollution, noise, and danger while compromising their access to shade, water, and walkable space.

This infrastructural violence has adversely affected the intimate connections between people and nature and accelerated the crisis, which Soga and Gaston (2016) termed as ‘extinction of experience.’ One respondent nostalgically recalled, “muje aaj bhi yaad hai wo signal ka laal hona aur mera bhagtay huye road cross kar keh pani main chhalang lagana” (I still remember when the signal turned red, and I would run across the road to jump into the canal). The traffic signal was more than a regulatory device; it was an enabler of a basic urban right for pedestrians, allowing them to access and interact with urban nature along the Lahore Canal. The signal-free corridor has erased this possibility, granting vehicles dominion over a space that was once shared.

The infrastructural changes along the canal not only reduced the green footprint, but have changed the perception of urban nature spaces. One respondent lamented the disappearance of the vibrant red flowers from the Sanober trees that once lined the canal each spring. The loss of these heritage trees, what Roudavski and Rattan (2020) describe as critical anchors of urban identity which shapes the relationship of people and nature in the city. Simultaneously, the loss of the objective form of nature and increase in the grey infrastructure have caused the production of detrimental ecologies: intensified noise and air pollution; decreased the carbon sequestration potential; heightened the sense of insecurity; disrupted bird and other fauna habitats; and fragmented what was once a continuous green corridor while hindering species movement. The Lahore Canal road-widening thus reveals how narrowly framed, car-centric urban development deepens social and ecological vulnerability, which directly impacts often-overlooked stakeholders who depend on the canal, not merely for the aesthetic value of urban nature but for survival. These conditions might worsen under the recent proposal to develop a metro-line along the canal.

The case of the Lahore Canal calls for a fundamental reimagining of the urban development paradigm. The canal, in its liminality and informality, is not outside the city’s ecological system, rather, it functions as a vernacular climate infrastructure, sustained not by formal design but by citizen’s daily interaction with space. This interrelationship of coexistence is not abstract, but a response to thermal, spatial, ecological, and socio-environmental inequities, depicting how both human and non-human life endure hostile climates under the conditions of neglect. For those who rely on the canal’s liminal green spaces in extreme weather conditions, climate adaptation is not a future policy, but an ongoing process defined by three critical practices: first, inhabiting — embodied, everyday interaction with urban nature spaces in the search of alternatives for respite and survival; second, negotiating — the space appropriation and transformation carried out by social agency; and third, preserving — collective and individual acts of care that sustain the broader human and non-human ecologies. As cities in South Asia grapple with intensifying environmental pressures, the forgotten and sidelined liminal urban nature spaces, such as the Lahore Canal, offer lessons for an alternative future rooted in coexistence, adaptability, care, and empathy which challenges the homogenous vision of the world-class city.

Alam, R. and Shirazi, S.A. (2014) ‘Spatial Distribution Of Urban Green Spaces In Lahore, Pakistan: A Case Study Of Gulberg Town’, Pakistan Journal of Science, 66(3).

Anguelovski, I., & Connolly, J. J. (2024). Segregating by Greening: What Do We Mean by Green Gentrification? Journal of Planning Literature, 39(3), 386–394.

Azhar, R. et al. (2024) ‘Urban transformation in Lahore: three decades of land cover changes, green space decline, and sustainable development challenges’, Geography, Environment, Sustainability, 17(2), pp. 6–17.

Cervero, R. (2009) ‘Transport Infrastructure and Global Competitiveness: Balancing Mobility and Livability’, The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 626(1), pp. 210–225.

Harris, A. (2013) ‘Concrete geographies: Assembling global Mumbai through transport infrastructure’, City, 17(3), pp. 343–360.

Riley, S.P.D. et al. (2014) ‘Wildlife Friendly Roads: The Impacts of Roads on Wildlife in Urban Areas and Potential Remedies’, in Urban Wildlife, pp. 323–360.

Roudavski, S., Rutten, J. Towards more-than-human heritage: arboreal habitats as a challenge for heritage preservation. Built Heritage 4, 4 (2020).

Soga, M. and Gaston, K.J. (2016) ‘Extinction of experience: the loss of human–nature interactions’, Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 14(2), pp. 94–101.

Shoaib, A. et al. (2022) ‘Assessing spatial distribution and residents satisfaction for urban green spaces in Lahore city, Pakistan’, GeoJournal, 87(6), pp. 4975–4990.